Nico Malaspina: A young Milanese filmmaker looks to future, Da Vinci in pocket

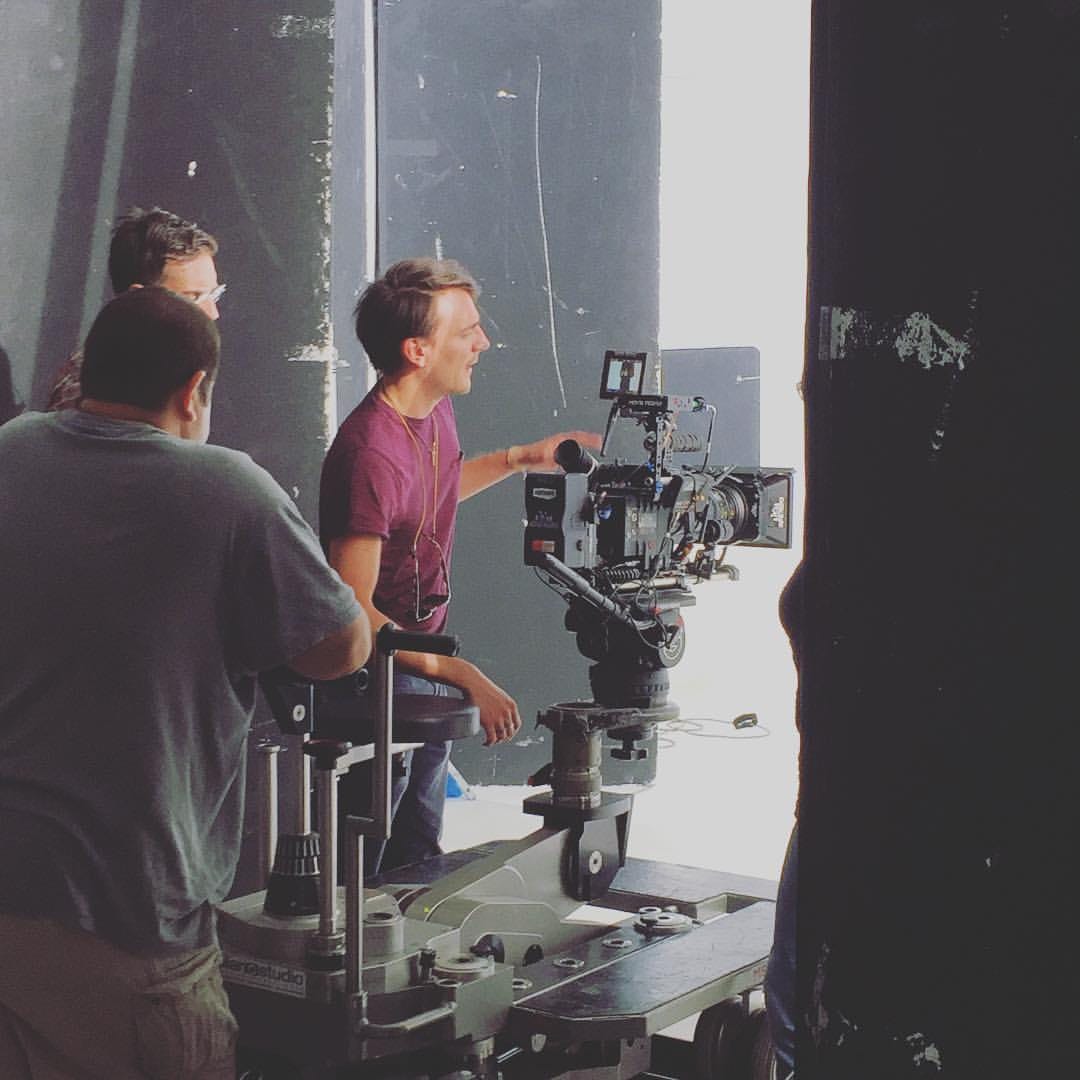

Since early train-yard graffiti to songwriting, a director’s camera pans across eclectic sets, ideas brewing

Long before directing a film on Leonardo Da Vinci, Nico Malaspina tagged greater Milan’s railway sidings.

“I truly loved the atmosphere of being at an abandoned train yard in winter with snow,” says Malaspina, sipping a frosty microbrew on Friday. “I needed to go out into the world and do something not programmed. Graffiti is a type of art.”

Graffiti, an Italian word etymologically tied to scratch marks, itched his urge to wield more than half-foot-long pens and spray-paint cans, giving way to moving-image tools capable of depicting art beyond colorful scrawls.

“I realized I could express myself with a camera,” he says. “I had the fire.”

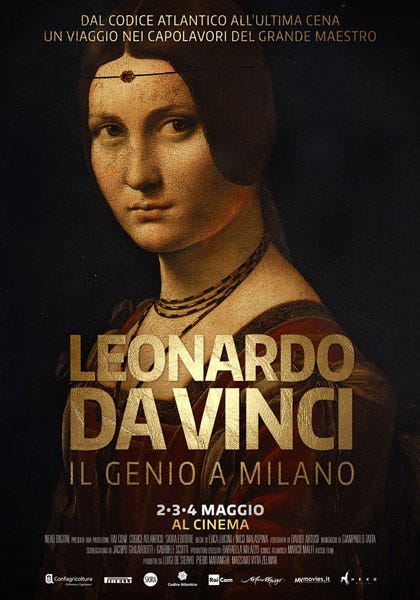

His desire paid off in 2016, when he was tabbed by mainstream Italian filmmaker Luca Lucini to co-direct a documentary, “Leonardo Da Vinci: the Genius in Milan,” which played in cinemas across Italy, with distribution worldwide, he says.

The 33-year-old native of Milan has since crafted short movies, music videos and TV commercials, but his long-term goal is to make a feature film.

“That’s why I’m trying to swim in the big ocean,” he says, slipping into allegory at Franco’s Pub, steps from Bocconi University, where a business crowd is letting out into muggy 99-degree haze, the summer’s hottest to date in Milan.

Fiddling with a two-piece cigarette, he is talking shop with a music producer, Luca La Morgia, 30. As with rolling cigarettes, making films is tricky, Malaspina says, putting wrapping paper to tongue, thumb and index finger to filter. He recounts care-free days at his Milan arts high school, when he found himself up to teen-spirit mischief until catching the camera bug. After coming home from the yards, he would put pen to paper and, later, play guitar lyrics. Along the way, he discovered film would lend even greater expression to his art.

Italians generally stay close to home when attending college, but Malaspina’s school took him several region’s away, to Rome’s NUCT: Scuola Internazionale di Cinema e Televisione.

When in Rome, rolling to action requires more than fiddly attention to detail, confesses Malaspina, who views film through the lens of a director who has seen both cinema worlds.

“There is more meritocracy in Milan: You don’t need to be anybody special to start your ‘journey.’ ”

The two titan cities have cultures that have long clashed. Milan’s got fashion, financial institutions, two tough soccer clubs and La Scala opera house. Rome’s got the Vatican, the Colosseum, governmental offices and famed Cinecittà film studios.

Several in the pub are wearing cargo pants and black T-shirts, outfits contrarian to Milan’s staid suit-and-tie aesthetic. Dressed like a north Brooklyn transplant, Malaspina springs up at spotting a peer: “Wait, I know you.”

Minutes later, he takes his Yankees cap back off and resumes smoking at the table, with a body language vacillating between hyperactive and chill.

“It was a just a coincidence,” he says in English, explaining the city’s tight-knit movie-set community. “Once you get in, you know everybody.” He founded Grizzly, a collective whose members spread the word when a film project is about to take off, providing work, as in a guild.

He and La Morgia request appetizers, an integral part of Milan’s happy-hour culture.

“Could we get two types of bruschetta?” says La Morgia, a composer and music producer who collaborates with Malaspina on videos and short films. As soon as the anchovies- and sausage-topped bruschetta are chewed, he wryly explains their lure, with what looks to be white cream on toasted bread.

“Of course, it’s good,” he says. “It’s lard. All fats are good. When you fry something, it’s good.”

Obsesssed with tunes night and day, he is fresh off seeing “The Smile,” an English rock band that played the evening before at Fabrique, a popular Milan concert venue.

“It was sick,” he says, using slang. “Their stuff touches you.”

La Morgia is touched by audio and visual production and, like Malaspina, has earned recognition through a big-time production, his from a network series, “The Voice of Italy.” Broadcast on state-owned TV channel RAI 1, the show on singing pits competitors against one another. As a producer, La Morgia stylistically arranges the music sung, coordinating logistics from start to finish with the musical director and band.

He will carry on with the same role in the series sequel, “The Voice Senior,” scheduled to air in September, he says.

Passionate about cooking, he grew up in Pescara, Abruzzo, a region of central Italy.

“I can do a great ragù di polpo (octupus),” says La Morgia, married with two kids. They get to eat his other specialty, slow-cooked rabbit, stewed in olives, capers and aromatic herbs.

“It’s going to melt in your mouth,” he promises, simultaneously checking on his children via phone.

“Family gives you balance,” he says, citing long hours tied to hectic music production.

With his earnings, Malaspina bought an apartment in the north Milan neighborhood of Certosa, where he lives with his girlfriend, Sofia Pauly, 35, an actor. She tolerates his hard-core devotion to Milan’s Inter football club.

“When there’s a match, everything stops,” says Pauly, who is Italian and half English, from London. “I’m not really used to it.”

After graduating from film school, Malaspina had gotten used to twiddling his thumbs off set, away from cues for lights, camera, action. After a year and a half in London, he received an offer he couldn’t refuse, in 2015.

A NUCT professor, one Luca Lucini, had seen potential in him, convincing Malaspina to move back to Milan at age 25. Soon, he was shooting second-unit scenes for a documentary on La Scala opera house, with Lucini at the helm.

“He kept me under his wing,” Malaspina says.

The shooting of “Leonardo” rolled around, with one small challenge: Lucini was seeing to a second film and needed someone to take the reigns for the movie on Da Vinci, the eclectic artist and engineer who worked in Milan in the late 1400’s, when he painted the “The Last Supper.”

With Lucini at his side, Malaspina learned on the job.

“I didn’t know where to start,” he says. “He helped me a lot. I will always be grateful to him.” Lucini, 54, has made 13 feature-length films for cinema.

Lucini, shooting a film in Naples today, said he was struck by Malaspina’s lucidity, interpersonal skills and calm demeanor at a NUCT course that required technical aptitude, uncommon traits in a director as young as Malaspina.

“It seemed natural and useful to do (the film) together because I needed someone who was capable of handling it seriously,” said Lucini through a text message, adding Malaspina was someone he “could trust.”

Malaspina has parlayed the experience into a steady stream of music videos and short-film projects, some done with La Morgia, that entail making mistakes on the path toward perfection, rather than receiving instant gratification and accolades.

“You have to fail at first,” says Malaspina, grounded in knowing a second big break might only come through a nose-to-the-grindstone mentality, on big-city streets where competition is thick and funding thin.

The next few days will see his clapperboard cutting takes for two TV commercials to be aired on network channels, with stores keen on selling apples and assorted produce in a country whose citizens value healthy food, evidenced through their comparatively slender figures, like Malaspina’s.

Malaspina, who grew up in Mazzo di Rho, two metro stops from Milan proper, is in the early stages of writing a short film centered around an Asian seamstress, a work he sees falling under the genre of magic hyper realism.

He looks to such filmmakers as Paul Thomas Anderson, an American, for inspiration: “He does things I don’t know how he does.”

His commentary shifts to Italy, where getting a feature film screened is a process fraught with road blocks, he says.

“In America, at age 23, you can make a movie. Here, it’s like a game at a young age. It’s not easy because we don’t have the same industry.”

In a Covid era where movies and series are streamed at home, Malaspina laments scriptwriting and plot development that, he says, are short on originality: “They are cooked, like a récipé. The attention to the story flies away. It’s like an algorithm.”

With creativity and distribution at a juncture point, he predicts a renaissance of sorts in the next five years. The mystery, he says, is figuring out what it will be.

“We are on a bridge, a turning point,” he says, turning back to his dreams, ever stirring.

“I want to do stories. I want to do narratives. You need money to make a movie. Ideas come first, then courage.”

-30-

Yes, Malaspina’s spontaneous. His mind turns.

These energetic young creatives! They make me feel old and tired. (Maybe because I am.)