Pavia: once capital of Italy as we know it, where a continental king was crowned and a ‘volt’ jolted the world

You got a soft spot for college courtyards and Holy Roman emperor coronations? Who needs “Game of Thrones” when the real stuff is a €3.60 train trip from Milan.

Nov. 28, 2022

The little city that could.

Would Cambridge’s courtyards have squared without inspiration from the unheralded college town minutes from rice paddies? It might also be worth noting: That hand-held device of yours uses a battery.

And so?

Your avatar owes gratitude to the Lombardy city where a scientist tinkered with “piles” of current before finally cobbling together the world’s first battery.

Digital browsing needs power so let’s pile a little praise on Pavia, the low-plains outpost that’s a vigorous medieval march from the Alps, over which ogres traipsed to a quarrelsome land.

Over centuries, even millennia, Pavia has seen impactful events, hegemonic invaders included—all stuffy history sniffed at by even stuffier modern-day Milanese pining for VIP glamor. Pavia is pretty much written off as a tourist destination, lacking proper head-turning pizzazz: the Ferrari kind found at Bellagio and Sirmione, where lakeshore breeze accompanies posh tilts of Prosecco savored too by Wall Street wolves, lovers at their side.

The bourgeoisie can pay €3.60 for a half-hour train trip from hipper Milan to sleepy Pavia, where stony streets lead to quixotic college quadrangles enlightening the curious. Medieval kings, too, were crowned in the river town, making it de facto capital of de facto Italy, once upon a time, when Rome had yet to emerge from the Dark Ages.

Places like Pavia help “connect the dots,” as Steve Jobs so famously said at a Stanford University graduation ceremony, so who needs fictitious TV series about dragons when north Italy has its own monstrous cast?

More than a thousand years back, the Vatican played second fiddle to Germanic noble Charlemagne. Then came an ambitious king named Barbarossa, further shaping The Holy Roman Empire, which the ‘Church’ needed at its side.

Far away from Rome, Pavia’s prestige slowly blossomed under Arian Christian Lombards, descendants of German tribes. To put it too simply, some north Italians ended up with pointy noses, sharply seen today among a Milanese or two.

Still, as my Western Civilization professor said during my very first college class, in late September 1986 at the University of Oregon:

“The Holy Roman Empire was neither Holy. Nor Roman. Nor an Empire.” We 150 students and she were talking about what constitutes a ‘civilization.’

Check mark.

History was not on my mind when I inquired today of a greying Italian whether the city of 73,000 might have a tourism office with maps. No, it did not, he genteelly said, before getting cut off by a passing middle-aged Italiana, eager to help. She wanted to speak English but I insisted on her native tongue.

“Try a bookstore” was her gist. I bid her a nice day and soon stopped another woman, who was walking her dog. Lunch time was nearing.

“Fried frog legs? Yes, we’ve got them, but you’ve got to go a little outside the city to a trattoria near the River Ticino, where they make them freshly.”

“But I don’t have a car.”

“Oh, no. Nope, you can’t get them in the city.” She did, however, recommend a small reasonably priced restaurant that serves up hot dishes as well as succulent sandwiches. The locals always know the good places.

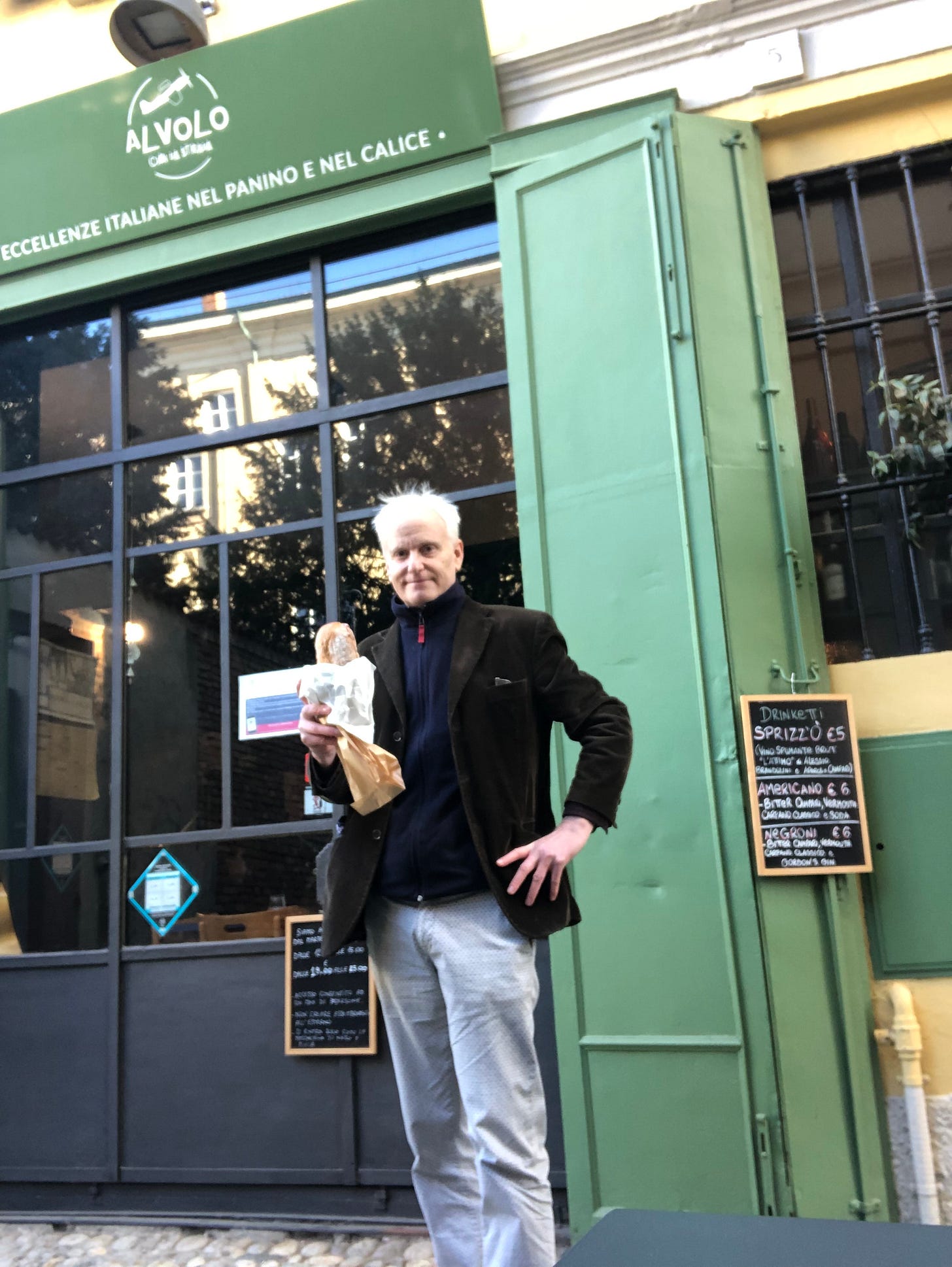

Frog legs, a specialty of the region, would have to wait. My maternal granny ate them in southwest Missouri as a girl during The Great Depression. I still don’t know whether they taste like chicken, but I’ll eat them in any economic climate. My third visit to Pavia, which I hadn’t seen in 10 years, would take me in a 10-kilometer circle after lunch at Al Volo, tucked away on a side street.

The lady with the dog was spot on. I ordered something called a Fidati—“Trust me” could it be?—a scrumptious sandwich layered with creamy Gorgonzola cheese, so-called Tuscan bacon, and razor-thin slices of lemon, with peel.

At Al Volo, a handsome display of local wines greets customers, who line up for lunch. I was the first and got my panino—presto.

A tiny seafood sensation teased my tastebuds, and the reason stumped me until checking the ingredients again, and there it was: anchovies, of all things.

An orange tamed my stomach’s rumblings. When you are 54, you learn to eat healthily. Italians prioritize eating fruit, which sells cheaply.

Far away from my beloved Eugene, Ore., state-school campus, I gravitated toward University of Pavia, just up the street. Dating to 1363, it is among the world’s oldest universities.

What Italian colleges lack in lawns ideal for frisbee throwing, they often make up for in lavish interiors, resplendent with hallowed corridors through which scholars roamed while speaking a mix of the local language as well as Latin, like their English counterparts.

Laying claim to inventions has always been a bit of a sore point for Italy, which may have had a couple of its best innovations stolen away, such as the telephone, conceived by Antonio Meucci. Alexander Graham Bell ended up getting the patent.

A scientist named Alessandro Volta, however, would suffer no such dispute, inventing the electric battery and discovering methane about the time the US Founding Fathers were busy fending off Britons. Volta—hence, “volt” in English— would go on to chair Pavia’s physics department for 40 years.

The statue of its most famous academic sits center square in one of more than six quad courtyards that carry a wanderer hundreds of yards. Some are roofed while others are open air, serving as study areas for sunlight-deprived students. Thick ivy snakes over and up walls and rails, and the occasional tropical palm tree shades study-wary scholars when winter gives way to spring and then summer, which happens in a hurry here, where July humidity soaks shirts in a jiffy.

Today, I thought of the film “Chariots of Fire.” Two Cambridge undergraduates vie to round the portico of a quadrangle before the bell tower’s bong signals time’s up.

The quads at Pavia would challenge world-class sprinters if such a contest took place. The longest straight-away porticos cover at least 150 yards, and the two ‘shorter’ sides of the quad are about 40 yards long. Let’s just say 400 yards on slick granite, with four nasty turns.

Just outside the quads stand three brick medieval towers, standing roughly 10 yards from one another. Their purpose? They are a reminder on who has had enduring power and wisdom, bridging peasantry to the Black Death to Napoleon to world wars. The towers don’t change.

Christmas comes and goes. Imagine, like Rutger Hauer in “Blade Runner,” what they have seen?

During a short break to rest weary legs, three green grosbeaks swooped around the towers like children pestering each other on a playground. The triple torre, alone with their thoughts, stood immortal to the commotion. Few tourists pay their respect.

“Where have all the minstrels gone?’ the towers might say. “Remember the times when wooden carts, stacked high with cadavers, crept by through the night?”

No jaunt to see Romanesque shrines would be complete if it excluded the church where an emperor of vast swathes of Europe was coronated. San Michele would have been missed had it not been for a young father, dressed like an investment banker, who confirmed the basilica is tied to Pavia’s glory days—which came generations after Charlemagne’s troops obliterated a citadel belonging to uppity Italian king Desiderius.

“Go there,” he said, juggling his two toddlers like a minstrel.

San Michele, unlike the towers, is flaking away on the outside but remains resolute inside. The lone white church in the area, it was built from sandstone in the 11th century and hosted the crowning of Frederick Barbarossa in 1152 anno Domini. He became king of Italian lands and the Holy Roman Empire, which extended across much of Europe.

In the crypt, a sculpted man frowns as two demons gnaw at his shoulders, as if an invitation for mortals to high tail it out.

Feelings of hunger, thirst and fatigue set in as a longing stirred within me.

“Next time back, I’ll get those frog legs.”

-30-