Petra Sijpesteijn: Put the key to the door, receive a push, fight back with a choke

The professor of Arabic reflects on papyrus, #MeToo and why the Islamic Golden Age gets little attention. From University of Oregon to Oxford, high jumping and crew shaped her take on life.

In 1995, Sijpesteijn fended off an attempted sexual assault in Damascus, Syria, where she was an exchange student. On a visit to Milan, the professor of Arabic explores the courtyard at Santa Maria delle Grazie, outside of which Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” mural exhibits.

The ex-college high jumper clamps both hands to her foe’s throat and begins to choke him until his eyes bulge.

Rational, she releases her grip.

“I didn’t want to kill him.”

Six-foot, slender and deceptively muscle-toned, she makes a leap for the stairs. At this point, she is breathing hard. Just up one short floor is the apartment, her refuge from mayhem. She can do it.

Or can she?

The young man with the manicured “George Michaels” beard, as she calls it, shakes off the momentary strangle and won’t take no for an answer. In his 20s, he is wearing a zipped-up waist-length black leather jacket and lunges again, like a zombie reaching out from fresh earth, intent on rape.

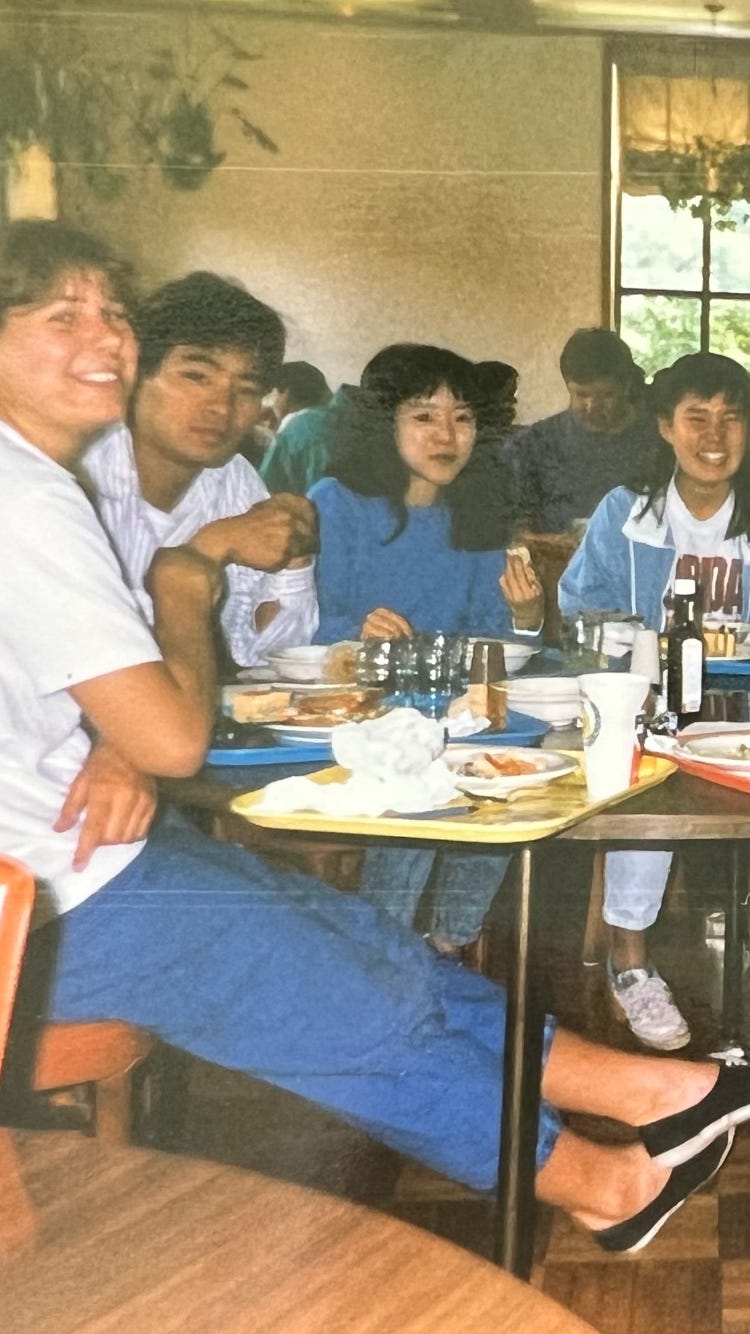

A half hour earlier, Petra Sijpesteijn was chatting with a potpourri of college friends passing around finger food and drinking soft drinks at a low-key dinner party in an upscale neighborhood of Damascus, Syria. It was getting late, near midnight, but she’d made arrangements to stay at a friend’s place because the gates to her university dormitory would be closed.

In Damascus, Sijpesteijn became fluent in Arabic and attended house parties with University of Damascus students (photo: Sijpesteijn archive)

Sijpesteijn at the Aleppo mosque in north Syria (photo: Sijpesteijn archive)

On a pleasant spring 1995 evening, she was dressed in tight pants, high heels and a sweater. She liked to do things her way, wearing what she wanted while reluctantly adapting to Damascus’ conservative cultural norms. She once gulped a cup of ceremonial tea to swiftly satisfy social protocol at a university event. Another time, she offered care-package cookies to passing dormitory mates, with the caveat they take them at once or leave them, eschewing customary humming-and-hawing on offers of cuisine.

“I was quite confrontational,” she says. “I didn’t adjust my behaviors.”

The Dutch undergraduate, however, was quickly becoming a capable speaker of Arabic, a powerful tool, she would discover the final few months of her year abroad at the University of Damascus. The Leiden University exchange student with the short “dirty blonde” hair went out to hail a cab, which within minutes would take her to a street lined with consulates and embassies, including the Netherlands’. It was supposed to have been an uneventful cab ride.

***

Twenty-eight years later, the tale of that #MeToo encounter, broken down into oral chapters, merits a short break.

On Saturday, she took the high-speed Frecciarossa train from Turin to Milan, where she shelved research for a day as a tourist.

Fresh off the train from Turin, Sijpesteijn sees Milan’s Duomo cathedral.

Sijpesteijn visiting the entrance to Milan’s Ambrosian Library, where her mother did research more than 60 years ago.

Sijpesteijn, 52, chairs Leiden University’s Arabic studies department, more than 400 years old, and is spending two weeks away from family. At Turin’s Egyptian Museum, she is doing research on Arabic writings on papyrus, a specialty of hers.

In Milan, a swill of something strong is in order at a café a short walk from “The Last Supper” exhibit, sold out as always.

“I’ll have an espresso,” Sijpesteijn tells the waiter at a sprawling shaded patio around the corner from Università Cattolica, where undergraduates are huddled over cocktails on a balmy afternoon, forgetting their studies as April builds toward Easter.

The bespectacled woman who says “Van Gogh” the guttural way is embracing sun rays, part of her perpetual joie de vivre, discovered over three decades across the Middle East, Europe and the United States, through ancient libraries, at college track meets, over English rivers as a crew-team rower, at archeological dig sites, during teas within prestigious universities, and in college classrooms full of eager learners.

She is married to Alex, a New Zealander. The couple has three sons and a daughter. On a day when a painful story is rehashed, she is equally perturbed yet amused by recounting how adopted soccer balls litter her Leiden back yard, where her long foot recently thumped two into an adjoining canal, a message to her second-oldest son to ease up on the round mongrel leather collection.

“Every time I come home, there seems to be another ball,” she says, chuckling easily while sampling a mini bruschetta. Her words transition back to papyrus.

She came to Turin out of curiosity when a colleague urged her to check out the museum. Turin’s is considered among the best in the world, outside of Egypt.

“It is the Indiana Jones in me,” she says. “You never know what you will discover.”

As is often the case, she has been examining papyrus sheets tied to such everyday life as: a 9th century marriage contract; letters from merchants; a poem; and a few receipts from the first 100 years of Muslim rule in Egypt.

Sijpesteijn studies ancient papyrus letters, written in Arabic, that provide a look into private lives and administrative matters (Photo: Sijpesteijn archive).

As in paleontology with T-Rex and in archeology with King Tut, the next treasure might be a step away.

The professor of Arabic, by now fluent, has the same strong shoulders as she had as a 19-year-old at the University of Oregon, where her college days began. Long sturdy fingers, the type that would come in handy during a scrap, dwarf the petite espresso cup, filled with black coffee, a word fittingly derived from Arabic and Dutch.

She takes a sip, leans forward while eyeing her purse and returns in spirit to Damascus, across the Mediterranean from Italy.

***

Sijpesteijn steps into the back seat of an empty cab in Damascus, a city of two million inhabitants. The taxi quickly stops to pick up another passenger, a young man who takes a seat up front.

When she gets out and puts the key to the outside door, someone is close behind. A shove sends her into the lobby, and a spontaneous rumble is on.

“We fought,” Sijpesteijn says. “I was physically definitely stronger. He tried to get hold of me so I pushed him. At some point, I slipped. I was on the floor. At the beginning, I held back a bit.”

In Arabic, she tries reasoning with her shorter assailant:

“Mish biddi!” - I don’t want (to)

“Khalini!” - Leave me (alone)

“Ruh!” - Go

“Síbni!” - Don’t touch me

Her pleas fall on deaf ears, but she breaks free and makes a go for the stairwell, with her sweater grossly stretched.

“But he pulled me back down the stairs. That’s when I thought I really have to get out of this. I took him by the throat, and I held him, standing. I was winning.” Fearing she could suffocate him, she relinquishes her grasp, and the brawl turns into a no-holds-barred wrestling match.

Balled up onto the floor like Greco-Roman grapplers, the two are pushing, kicking and grabbing at each other. At a certain point, she remembers, no words are exchanged, just blows to the chest, shoulders and limbs, when an aura of barnyard grunting filled the dark lobby.

“There was no more talking, just fighting,” says Sijpesteijn, mimicking the fatigued breathing that accompanied the tussle.

She has again tired out her attacker.

“I got up, and I was just holding him at one point,” says Sijpesteijn, who did competitive team sports at two different colleges. One event, the high jump at the University of Oregon, required strong leg lift and technique. After the stay in Syria, she was doing so well at rowing as a 30-year-old, she began to reconsider her career in academics after helping spearhead a University of Oxford crew team to a series of victories, drawing on upper-body strength, stamina and, again, execution as precise as a freestyle wrestler’s go-to pin move.

Clearly, says Dutch friend Sylvia Huisman, who studied together with Sijpesteijn at UO:

“That guy picked the wrong girl.” Her eyes light up.

The pair had clowned around together in Eugene, Ore., engaging in sisterly play-housing when away from UO classrooms.

Far from play-housing, Sijpesteijn at last extracts herself and climbs the stairs leading to the Damascus flat.

“It must have been uncomfortable for him because that’s why I got away.”

For the second time, she turns her key to a lock, this time through the door belonging to the apartment owned by her Dutch friend, a woman in her 30s who is sound asleep.

Relieved she has made it inside, she moves to quickly shut the door but—guess who?—just won’t go away?

“I was inside and he put his foot between the door. It was like one of those horror films when you think they’ve made it (to safety).”

The commotion wakes up Sijpesteijn’s friend, who comes running out of her bedroom to ask what’s going on. The prospect of having it out with not one but two fighters has at last scared off the relentless perpetrator.

“I guess it was too much to take on two Dutch women,” she says.

Sijpesteijn, left, fought to get up to her Dutch friend’s apartment. Here, she is attending a party at a U.S. Marine Corps bar in Damascus (Photo: Sijpesteijn archive)

The next day, her friend accompanies Sijpesteijn to the Dutch embassy to file a statement. Having cleared her most dangerous threat, she now faces a whole new round of obstacles, putting her Arabic to the ultimate test—voiced at a police station, where hardened faces with preconceived notions on Western women ever steel the 24-year-old “confrontational” college student.

***

Having polished off the espresso and revealed the crux of her ordeal, Sijpesteijn absorbs the laidback vibe and college-crowd din. It’s time for a real drink, she says. Sijpesteijn has plenty to smile about, despite the story on Syria that plays out with traces of “The Night Of,” a mini series on the many layers of justice either gone wrong or never met, across diverse cultures and languages.

“I’ll take a Spritz now,” she says during happy hour proper, called aperitivo in Milan. Her drink is accompanied by a thin-crust Roman-style pizza, an appetizer that comes with the price of a beverage.

She cradles the cocktail glass of orange Spritz, lightly fortified with Prosecco, while pontificating on Arab culture and history, unjustly set to the side from mainstream education, she says.

With a Spritz in hand, Sijpesteijn speaks about the Islamic Golden Age.

“It’s a world that’s still considered to be far from ours even though it shouldn’t be,” says Sijpesteijn, who earned her master’s and doctorate degrees at Princeton University (Near Eastern studies, 2004) before accepting a four-year post-doctorate research position in Oriental studies at Christ Church College, University of Oxford.

Elected last year into the Institute de France, a society that honors academics across the world, Sijpesteijn chose a career tied to Arabic studies because she wished to illuminate the Islamic Golden Age, which flourished under caliphate rulers from the 7th to the 13th centuries, when Europe fell into the Dark Ages after the collapse of the Roman Empire.

She is the author of “Shaping a Muslim State,” Oxford University Press (2013).

“Why was that world thriving while we were crawling in the mud?” she poses. “Classical knowledge was preserved in the Arab world.” Innovation, too, took hold.

Vast achievements included the use of a compass to navigate a world believed to be round, crop rotation, the invention of the camera obscura, heightened surgical techniques tied to anatomy research, as well as the advent of today’s scientific method: hypotheses lead to experiments that result in conclusions.

Expert translation into Arabic of multi-tongued literature from far-off lands was centered in Baghdad. In 1258 A.D., the Mongols sacked the caliphate city and burned the book collection within the House of Wisdom, a precious library, signaling the end of the Golden Age and a catastrophic loss of written knowledge and art, scholars say.

It was said the Tigris River bled red and black: red for blood shed and black for the ink spilled from books.

Equally comfortable lecturing or hunkering down in libraries, Sijpesteijn helps make up for the loss of the House of Wisdom through the study of papyrus documents, most famously known in Egypt but found across the Middle East and the Mediterranean region. Papyrus is a type of thick paper made from a grass-like plant—also called papyrus—commonly grown along the banks of the Nile River. Wood-based paper came into vogue in 10th century China.

Sijpesteijn doing research on papyrus documents at Turin’s Egyptian Museum (Photo: Sijpesteijn archive)

Papyrus, she says, provides an insight into commoners’ routines that books don’t describe. Typically, they are letters on day-to-day matters that weren’t intended to be read centuries later.

“(Papyrus texts) give you a direct way into people’s lives: ‘Send us some apples because our mother is ill.’

“They are about the stories of women, the stories of slaves, of prisoners. You read what people wrote in the past: invitations to parties, commercial letters. It’s the same letter that someone wrote 1,200 years ago. They were written, read, thrown away and then dug up.”

As seen through her copious extracurricular pursuits across institutions, Sijpesteijn doesn’t fit the mold of an ivory-tower professor. Besides poking through library stacks, she has assisted in archeological digs in Egypt and north Syria.

During her Princeton years, she was on hand for two months at the excavation of Umayyad castle in north Syria when walls lined with golden stones and mosaic paintings were uncovered. In 2004, she looked on when a papyrus document on tax receipts was unearthed at the Fayyum Oasis in Egypt.

***

Ask and Ye Shall Receive

Sijpesteijn, right, with Dutch friend Sylvia Huisman during UO track practice at Hayward Field, 1990 (Photo: Sylvia Huisman archive)

Sijpesteijn and Huisman, center, with UO track team members (Photo: Sylvia Huisman archive)

When the 19-year-old exchange student gently rapped on the door, she didn’t know what to expect. She did know that asking is a harmless act and sometimes leads to fulfillment.

It was the office belonging to Tom Heinonen, the only women’s head coach to lead a program to multiple NCAA Division I titles in track and field and cross-country running. She came in, asked, and her request was granted: She could walk on to the team and compete in the high jump.

“If you don’t ask, you don’t get,” says Sijpesteijn, who has employed the approach throughout her life. “It’s a philosophy. I just knocked on his door and asked, ‘Can I train with the team?’ That set the whole thing in motion.

“I didn’t know (the track team’s) reputation, but people give you a chance.”

Her marks in competition topped out at five feet, 7 inches, she estimates, but she wore the UO singlet and was allowed to keep some of the gear, such as the hoody, when the season ended.

Carpe diem.

Sijpesteijn attended UO for a year via a Dutch educational exchange program, along with friend Sylvia Huisman, and tried to soak up as much US culture as possible, taking courses on theater, chemistry, biology, short stories, and history of the US South.

Her career goals sprouted in Eugene, when she one day told Huisman, 51, today an Amsterdam-area physician:

“I am interested in Arabic studies because I want to become a diplomat in an Arab country.”

The Dutch teen was outgoing too, says Catherine Coquan, who got a master’s in journalism at UO.

“I remember Petra as a tall, friendly, healthy girl who would happily join international parties,” says Coquan, who is French.

Sijpesteijn, left, with friends in UO’s Carson cafeteria (Photo: Sylvia Huisman)

In her UO dorm room (Photo: Sijpesteijn archive)

Good study habits, goals, will—and asking—led her to Cornell University in 1997 after graduating from Leiden University with bachelor’s degrees in ancient history and Arabic languages and culture. At Cornell, where she studied as a Fulbright scholar, she met her future husband.

That academic year, a Cornell professor recommended she apply to Princeton University. She asked a French friend to help prepare her for the math portion of the entrance exam, the GRE. She got in to her second Ivy League school and ended up getting a master’s and a doctorate degree in Near Eastern studies from the New Jersey college.

Then something extraordinary happened. While at the University of Oxford as a post-doctorate junior fellow in Oriental studies, she asked to join Christ Church College’s crew team.

In her 30s, a quandary emerged as she was helping her team to wins: Was she more suited to crew than pursuing a career in academics?

“I just decided to do (crew), and it really made me rethink my career,” says Sijpesteijn, who did the sport for two years. “In general, they are all 18 years old. I was 30.”

Sijpesteijn thrived as a rower for Christ Church College, at University of Oxford, as a 30-year-old post-doctorate research fellow (Photo: Sijpesteijn archive).

But life as a junior fellow had its benefits, including being able to carb up after burning calories rowing: Sijpesteijn was entitled to daily 4 o’clock tea at Christ Church College, with its scones and cream cakes.

Dinner was a fringe, too. As a fellow, she was permitted to sit “high-table” in the storied dining hall, with its dark-toned wood and etiquette requiring black gowns and grace said in Latin. As per tradition, undergraduates sit below fellows, who are also allowed to veer off the quadrangle courtyard paths and onto the grass—a privilege.

Her high-table dinner setting also happened to double as Hogwarts Dining Hall in the “Harry Potter” films.

The dining hall at Christ Church College, Oxford

***

Sijpesteijn has shed no blood but the bruising fight in the Damascus apartment lobby irks her enough to seek justice or at least tell her side of the story so as to speak out on violence against women.

Dutch embassy officials mince no words in recommending she let the incident go. Going to the police, they say, might see her visa get canceled and have her thrown out of the country, as has happened to other women who filed complaints, they say.

A tad crestfallen, she walks back to her embassy driver, Bushir, and tells him the news. A Syrian, he is “outraged” and tells Sijpesteijn he will go to the police station with her.

She has to weigh her options. Could the Dutch officials be right or should she stand up for her rights? She thinks it over.

“I had a fantastic experience (in Damascus),” she says. “They were lovely people. It wasn’t in my mind to make the country or the men look bad.”

At the same time, she has strong principles, a character averse to giving up, and believes silence is no answer to resolution.

Just do it.

Bushir and she walk into the head district police station, where a sergeant is tending to desk duties but invites them to sit down. A quick talk between the two men commences, with Sijpesteijn excluded from the conversation.

“We all know what foreign women are like,” says the sergeant.

Sijpesteijn is getting their Arabic. She already speaks two foreign languages fluently—English and French, with German coming easily enough—and is advancing with a third in Syria after a good seven months there.

She reflects for a moment on the foreign female presence in Damascus. It’s true. There are prostitutes from the ex-Soviet Union and other countries who fill discos and clubs, creating a loose impression on city streets. What would you expect the sergeant to say?

“The stereotype is they’re up for having sex with men, and they’re easier to get,” she says. As for the exchange students, “We were behaving more freely,” in the eyes of Syrians.

Bushir, though, insists on Sijpesteijn being allowed to file a statement. Before she knows it, she is walking down to the bowels of the station to who knows where. Without Bushir at her side, she enters a dim room resembling a sleeping quarters for multiple men or could it be a locker room doubling as a crude office?

A half dozen officers are propped up on bunk beds, and each is staring at her, it feels like, setting the scene for an awkward interrogation, she fears. Doing her best to screen out the unexpected company to her side, she passes a sofa and faces the far end, where an investigator is seated behind a desk with a landline phone, notepad and pen.

Dressed in a black uniform, he acknowledges her.

“Ok,” he says in Arabic. “Tell me what happened.”

Her words spill out. Sijpesteijn goes over the attempted sexual attack from start to finish, making sure to detail how she defended herself by momentarily chocking the man.

After nodding, the officer leans back in the creaking chair, clasps his hands and sighs deeply.

“You did well to come here,” he says. “Next time, keep on choking because it takes a long time before someone dies, and when they faint, you can get away.

“Strangle on for a bit more.”

A wave of solace passes through her.

“It was fantastic he reacted like that,” she says, “because it was indeed outrageous that it happened like that.”

“Next time, keep on choking . . . ”—Damascus police commander

Even better, the commander instructs an officer to drive Sijpesteijn around in an unmarked police car that evening in hopes of identifying the suspect. After weaving throughout the blocks near Sijpesteijn’s friend’s apartment and passing by cafés, ice-cream shops and well-heeled neighborhoods where young adults hang out, the officer behind the wheel opens up on reality.

“If you recognize him, it means that he’s part of the ruling elite, so it means we can’t do anything about it.”

Hafez al-Assad, father of current president Bashar al-Assad, ruled Syria in 1995. The family belongs to the Alawite Muslim sect, a religious minority in Sunni-majority Syria. An allegiance or tie to the Assad family means power and privilege.

Sijpesteijn in Leiden in 1992

***

At 6:45 p.m., the aperitivo-hour overflow crowd has now filled up the patio as Sijpesteijn moves on to walnut-sized fried treats, set on a separate wooden platter. “Oh, wow, these are good. What are they called?”

There is no need for dinner.

She does, however, need to occasionally stand up for her career choice, when confronted with the odd stranger or acquaintance who questions why a white Dutch woman is teaching Arabic studies.

“No one asks you, ‘How can you study Roman history when you are not a Roman?’ ” says Sijpesteijn, who does roughly 60 percent teaching and 40 percent research at Leiden University, where she has chaired the Arabic studies department since 2008.

“There is an unbridgeable divide.”

***

As far as she knows, her assailant was never arrested. That evening, Sijpesteijn takes the officer’s frank admission in stride. At a minimum, the police have been been sympathetic and helpful.

Having the courage to walk into the station and down to its basement was about sending a message that assaulting a woman in any country is wrong, she says.

“It was OK for me,” she says, “just to be acknowledged there were things happening. It really helped me to deal with my story. I felt (the police) were touched by my story.”

Sijpesteijn does take issue with how one of her Syrian dorm mates excused whistling and cat-calls at women.

Sijpesteijn’s University of Damascus dorm room (Photo: Sijpesteijn archive)

“She was always keen to put a positive spin on everything I said about Syria,” says Sijpesteijn. “That also explains why I was so keen to go the police.”

She is quick to point out that aggressive behavior targeting women is not restricted to certain geographical regions.

“The cutting line didn’t fall between Syrian men and foreign men.”

Never timorous, she resumed her Damascus routine.

“It didn’t impede the things that I did,” she says. “It happened because of some stupid Syrian man, but I am really grateful to some of the Syrian men and how they handled it.”

***

Sijpesteijn, like any professor, checks her watch. It’s time to roll on back to Turin, where papyrus is waiting.

Before she gets up from the table, she pauses:

“So yeah, I had my MeToo moment.”

-30-

Me too! Thanks for reading—DS

Scary story...I'm glad she was able to fight the guy off, and that he didn't come back. And I'm glad that the cops didn't act too horribly.