Sandy, Oregon: School fights shaped boyhoods, with flannel shirts tossed aside for fisticuffs.

In the Mount Hood town, kids worked out beefs on grass, asphalt. School sports couldn’t tame all locker-room adrenaline.

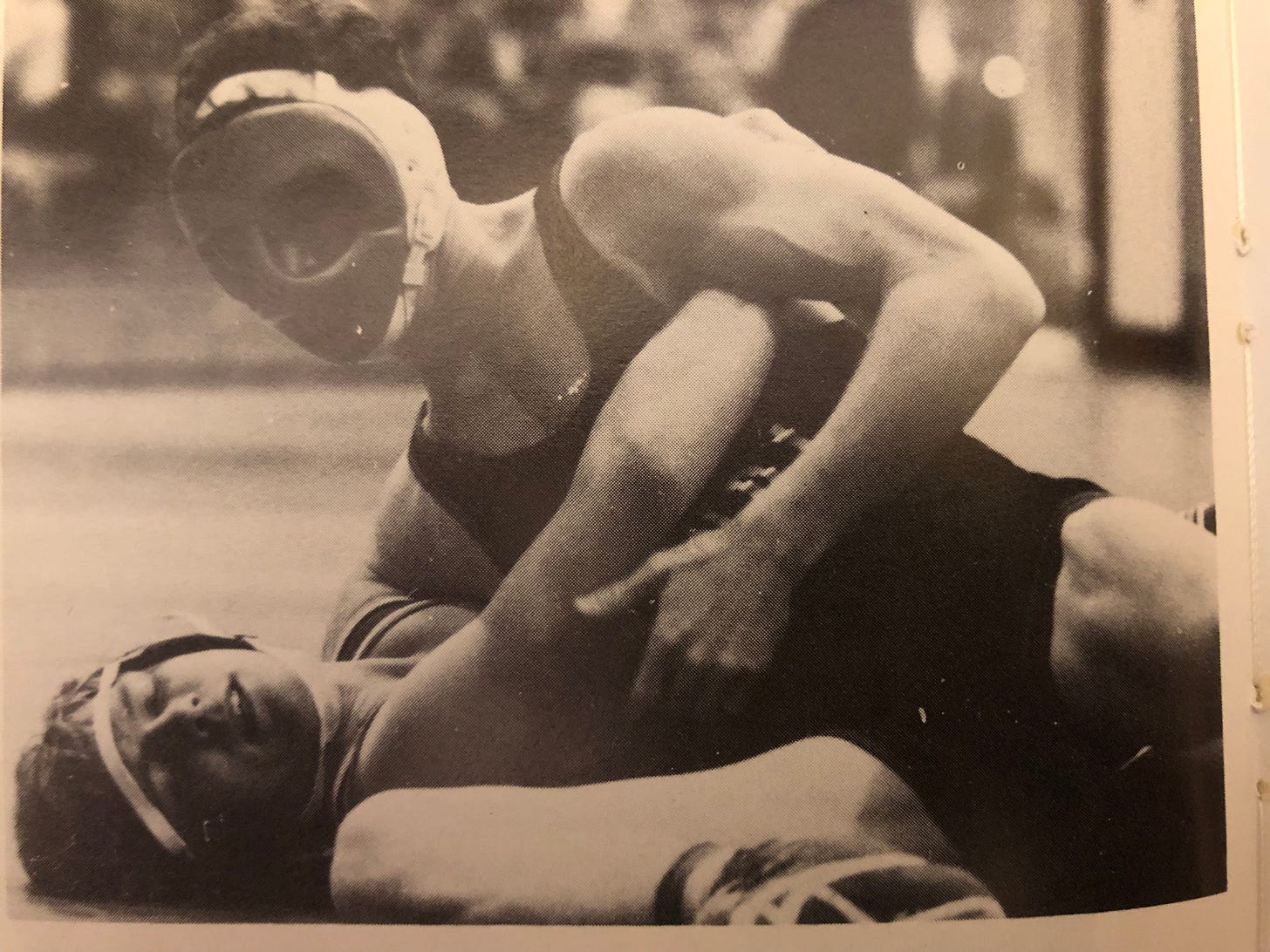

The Pioneers wrestling team, led in part by a masked grappler, had some kids who fought off the mat (photo: Ken Barton, The Sandy Post).

__________________________________

“Don’t make me hurt you so bad you have to call home to Mommy.”

Skilled at lobbing clever insults, the muscled blond kid was dressed in a crisp white T-shirt that read “Power Tools,” with a cartoon alligator’s snout as a saw. The other teen, six-foot and built like a quarter-miler, squared off during lunch-time recess near the play shed. His reason? Blond Kid, physically more mature than most, had unjustly beaten up a seventh-grader, slightly less buff.

Pick on somebody your own size.

Moments later, Blond Kid—the only one to generate the equivalent of a horse power running up steps during Mr. Barger’s physics class—landed a blow to the track kid’s eye-socket and walked away with a proud smirk, like Tony Robbins, as two-dozen junior-high boys looked wildly on, including me. Everybody knew he would star at Sandy High School as a football player, and he was also a good student.

There was no stopping him.

Lodged in most every middle-aged man’s head is the memory of childhood fights. What about you?

During the holidays, when nostalgia is rehashed with family and school buddies are bro-hugged, the good old days are shared via the oral tradition, about incidents that happened long before digital-message disputes.

Most times, fisticuffs are avoidable. Occasionally, they aren’t. Sometimes, they are fought mano a mano, with no onlookers. On outstanding occasions, young bystanders are willing cheerleaders, egging on the pair bound for a parking lot or ball field, as if a primeval instinct kicks in to prove who is alpha.

Early 1980’s Sandy, Ore., had its fair share of school-grounds fights. A small town with a fading logging culture, the Mount Hood corridor community was home to traditional jocks, blue-collar youth in flannel shirts, as well as a decent number of ‘hoods,’ shiftless teens who engaged in an underground economy, like Jesse in “Breaking Bad.” The cultivated commerce in Sandy, though, grew mostly among damp ferns and moss nestled deep within drizzly woods patrolled by snarly dogs, at the end of forgotten gravel roads off long loops like Wild Cat Mountain Drive, southeast of Sandy.

Like black and red ants vying for dirt, with a few fullback beetles joining the fray, school kids sought out Friday-night fights. Some took place off campus, as in the Paola’s Pizza parking lot, where a different blond kid—he with a normally shy demeanor—jumped on top of a car hood one night after a football game and pounded his chest like Tarzan, readying himself for a slug fest and fueled by beer.

The local Sandy Post newspaper in 1982 ran a political cartoon depicting two kids duking it out, titled: “After-School Sports.”

The school board had just axed Cedar Ridge junior high sports from its budget, and the paper’s message was clear: To fill the void, more boys were engaging in school-yard scuffles. The cult-classic movie “The Warriors,” about street fights in New York City, had been released a couple years back, coincidentally.

Mountaineers quarterback Gordon Brinser throws long in 1978. After-school sports gave Cedar Ridge students an outlet to vent steam before programs were cut in 1982-1983, a big year for school fights. Tall for an eighth-grader, Brinser was focused in the classroom.

__________________________________

Like wasps dislodged from a hive, the emotions that ignite teen brawls sneak up and strike at unpredictable moments. One kid provokes while the other puts himself into defensive mode. Settling festering beefs is not always the issue.

Two guys bumping shoulders on the way to class could just as easily flare tempers. Locker rooms, especially, were prime settings for dust-ups, some culminating in crude freestyle wresting, broken up a minute or two later by a physical education teacher or coach.

To be clear, I wasn’t a fighter, never have been. Sure, I threw one or two punches in grade school but nothing that got me suspended. Most of the time, I just walked away.

But—there is usually a ‘but’—I came close a couple times, and both occasions came either in or just outside the locker room.

The first happened when I was a freshman in P.E. We’ll just call the other kid Rob. He had been needling me for a few weeks, with the snap of a wet towel when a guy’s in a compromised position, or an ‘accidental’ trip during a P.E. 600-meter race, timed by Hutch, the track coach. Things were brewing between him and me, and ignoring him wasn’t working.

The final straw came while exiting the locker room, attached to the gymnasium. By some means or the other, he was goading me, likely through poke or push. At last, I pushed back, sending him backward into the bleachers.

Now, here’s the thing: Rob was tough—real tough—and would go on to dish out multiple beat-downs his four years at Sandy High. He could have pinned me right then and there, but he didn’t. As sometimes is the case when challenges are met, pushing back led to peace, and he left me alone from then on.

In fact, when we were seniors, he came up to me in the hallway and said to the effect: “Let me know if anybody ever bothers you.” We had achieved a sort of Zen-like understanding, when I was being accepted as a fringe cool kid, popular enough to be be invited to a keggar or two.

Rob was a wrestler and a good one. Most kids were scared of him. Blond Kid probably wasn’t but may have kept his eyes peeled.

The 1985-1986 Pioneers wrestling team, like every year, had tough kids. In 1982-1983, Sandy was runner-up at state, with University of Oregon scholarship winners, Chuck Kearney and Larry Topliff, placing first.

_____________________________________

Twenty years later, at our 20-year class reunion in 2006, Rob approached me, saying: “You know what? I apologize if I ever did anything bad to you in high school. What’ll you have?” That touched me. Haven’t spoken to him since, but the gesture sticks. If you are out there, Rob, thank you.

The second locker-room incident unfolded my senior year, when a hefty sophomore and I were arguing over a small locker. He challenged me to a fight. In great shape for long-distance track races but not much else, I let it slide. My friend Tonn, who scrapped on occasion, watched intently on.

“That kid is nuts. Good thing you didn’t fight him—but you know I would’ve had your back.”

One of the most talked about fights belonging to my class (1986) came during our junior year, when one of the school’s nicest students and most talented athletes was viciously attacked without cause in the restroom across from Mrs. Burgess’ English classroom. Blood spilled.

The alleged assailant, who could have been charged with assault, later cried like a baby when it came time to apologize, I was told.

For some kids, the foundation for fighting started in junior high, at Cedar Ridge, a 10-minute walk east of Sandy High. Word privately got around a quarter century ago that several of the Cedar Ridge staff considered my eighth-grade student body the ‘Worst Class Ever.’ Other teachers, no doubt, wouldn’t agree since every class has its good and bad.

However:

“Gentlemen, there’s something called insubordination,” our seventh-grade football coach, Mr. Pick said, as we all peered up toward the lower-level building. His eyes fixated on a lone uniformed player carrying his helmet while clowning around with girls. “What you can see,” Mr. Pick went on to say, is a distracted young man late for practice.

Consequences would be met.

Other scores were settled during classroom school hours.

Kean versus Luke, we’ll dub it.

Now, Kean was a commonly framed bean-pole teen, the type of kid who was middle of the pack, rarely standing out, a bump on a log. Generally quiet, he had a bone to pick with Luke or perhaps it was vice versa. The two agreed to fight it out on the football field, right where Mr. Pick had stood in astonishment.

News of the programmed lunch-time fist-fight tore across campus. Corn dogs, fruit salad, tater tots and chocolate milk had been consumed in the cafeteria. Leave that trey. It was time to witness a one-on-one rumble, Sandy-style, on muddy grass with slug slime.

The Mountaineers football field, where a highly attended fight took place during classroom hours.

_____________________________________

A legion of junior high-schoolers trailed the two during their march to battlefield. Luke was dressed in a button-down red-and-black flannel shirt, Kean similarly. Down to the track and onto the field they went, stopping near the goal posts. Broad-shouldered with a wrestler’s body rivaling Blond Kid’s, he flipped up tufts of thick brown hair every minute or so, pacing with a disconnected frown, alone with his thoughts while staring down.

Ten years later, while listening to Eddie Vedder scream in Pearl Jam’s break-out album, “Ten,” I realized some distraught Sandy kids carried a similar silent rage within them.

Kean raised his fists. Luke responded, with the crowd encircling the two. The fight was on. A couple three shouted out encouragement to Kean, gallantly standing his ground. Luke wound up like a baseball pitcher. His young blacksmith-like forearms rising, he took two steps toward Kean and lowered the boom, a clock-crunching round house.

Fist meets cheek.

Smack.

Kean went down like a teddy bear, and the stand-off was over in five seconds. His brow cross, the nearly stoic Luke turned around and walked back up the slope, with a dazed Kean shaking off the punch.

Later in the year, while in Mrs. Tomlinson’s English class, a stone the size of a baseball crashed through the window, stunning our class. I sat on the far side of the room.

“Stay in your seats!” the teacher implored, failing to restrain a curious few bolting to the window.

A solitary figure—who evidently had a canon arm—was walking away from the football field, a good distance from the Mrs. Tomlinson’s class, high above.

It was Luke.

-30-

Yes, I can understand this. That was back in the day when hazing was a little more accepted. It sort of took work getting out of fights. Mrs. Thomas! Good for her.

I was able to escape all fights, just barely. Once by telling my French teacher, Kathy Thomas, that a bully was waiting for me...she yelled at him. I had no shame at that age (and I wanted to get the hell out of Sandy).