Tank-busters, Where Art Thou? A Dirt Floor Wyoming Kid from Gillette Wants to Boss Folks Around Via Law

What does it take to be No. 1? Poverty makes or breaks a child. From dusty prairie to World War II misery to UP mail trains, a private finds a way. A tank-buster battalion patch defines his fury.

Walter Scott, second to right extending elbow, on family homestead outside Gillette, Wyo., circa 1923. His dad, far left, and mom, carrying kid, had Scottish and Irish blood. As in Ireland, potatoes were prized but grew too few on dusty terrain.

The army truck spins to an icy halt outside the Ardennes Forest, where American GIs are sniping at gray shadows within a twisted Wagnerian landscape.

“We never made it,” Walter Scott says decades later of the Battle of the Bulge, clasping his hands while looking out the living room window to Grand Avenue in the college town of Laramie, Wyo.

Destined to live to age 90, the retired federal judge works his jowls before sliding over to a cup of Folgers, poured as always into cheap china, the kind found at JCPenny. Black coffee, bacon and eggs, and butterscotch caramels are his vices. Vegetables be damned, fruit too. Camel cigarettes long ago gave him company, when a corporal’s thick fingers pounded out lantern-lit letters to families of the fallen on evenings under a tarp, when wind wheezed across a continent ripe with corpses.

After spryly crossing his legs and dangling an arm over the sofa, Scott comes out with it.

“Fact is, our driver was on the sauce and got lost,” he chuckles, partly in disgust. “What a boondoggle that was.” He reflexively passes a finger over his mouth to wipe off coffee residue and lets out a “Chee,” swiveling his head. This time, his jowls pulsate faster.

Grandpa doesn’t have much good to say about the war, slipping in a “Damn Roosevelt,” old-school Republican that he is. It’s no wonder he never drops in at the VFW, just up the street. Laramie is the type of town where old men meet up for donuts three blocks from the railroad tracks, at a breakfast joint on Third Street. He’ll put in a cameo appearance over coffee every now and then, slipping into I’m-uh-goin mode, vernacular picked up through childhood gabbing with Okie transplants. If he works at it, he’s got rancher’s charm—“Say, how many head you got out there?”—but wrath too often gets the best of him.

[Note: Two weeks ago, an online death certificate for Grandpa’s mom revealed she died June 2, 1944, four days before D-Day began, at the age of 63. He would have received the bad news right about then. “Ol’ Mom,” he once said to me in a soft trill, “she would tuck us in at night and sing lullabies.”]

Scott is reticent to divulge details on the carnage, the ghostly visages, the stench, the bawling—the horror, the horror. Nowadays, they are feelings lost on part of an avatar generation aloof to news on Russia versus Ukraine, too much maybe to digest when social media is a tap away.

No college kids in their right minds would watch “The World at War,” the masterful 1973 documentary narrated by theatrical Laurence Olivier. For one thing, they haven’t heard of it. “Saving Private Ryan” will just have to do.

Yet somewhere around the bend, from Russia to Japan to Germany to the USA, are vets soon to be centenarians. Do they still have nightmares, when the shriek of a Stuka dive-bomber or the hum of a B-25 Mitchell, sends them under one more sweaty cover?

A grandson’s question on death and destruction tied to the six-week Battle of the Bulge, when 19,000 Americans died, equal to a third of the Vietnam War’s toll on US lives, gets little out of him.

“Oh, I don’t remember much about that,” says Scott, peering back to Grand Avenue, where dually-wheel pickup trucks whir by. “That was a long time ago. You know, we were at the back of the lines.”

Steering the conversation toward war-time chow changes his tune, even eliciting nuanced comment.

“Well, I can tell you that I still remember the name for eggs and milk in French. It’s œuf andlait.”

As quickly as he cracks a smile, his expression sours.

“We had a hard time getting any type of food out of the French,” he says, “Why, it was the Germans—I’m talking about the civilians of course—who treated us better, and that’s the truth. You’d think it would be the other way around but it wasn’t. Some of those Germans, boy, they would come practically running. You know, we’d trade them a chocolate bar or a few cigarettes for a loaf of bread, a hunk of cheese, whatever they had.”

Grandpa ate plenty turnips growing up. K-rations were passable to his palate.

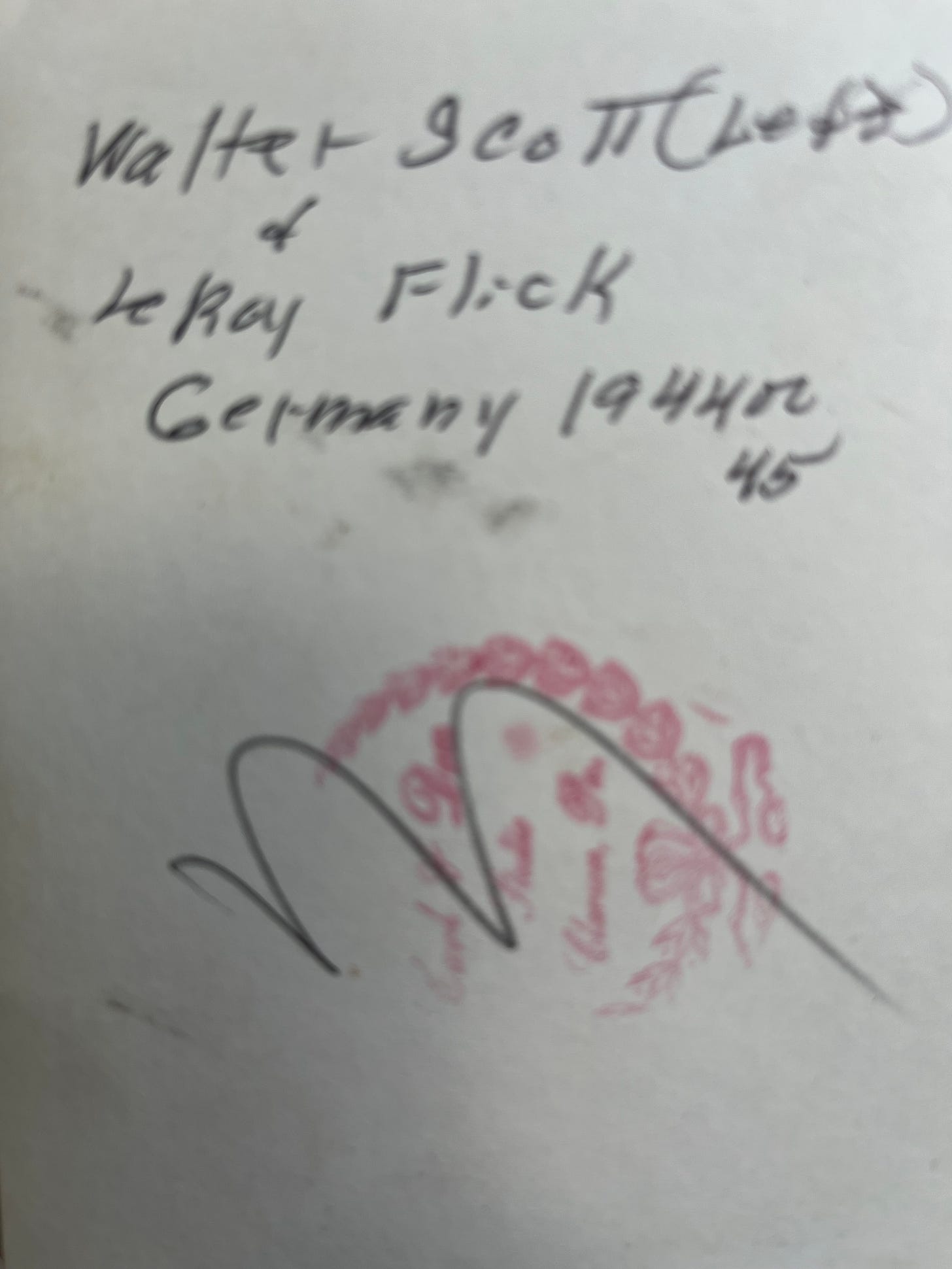

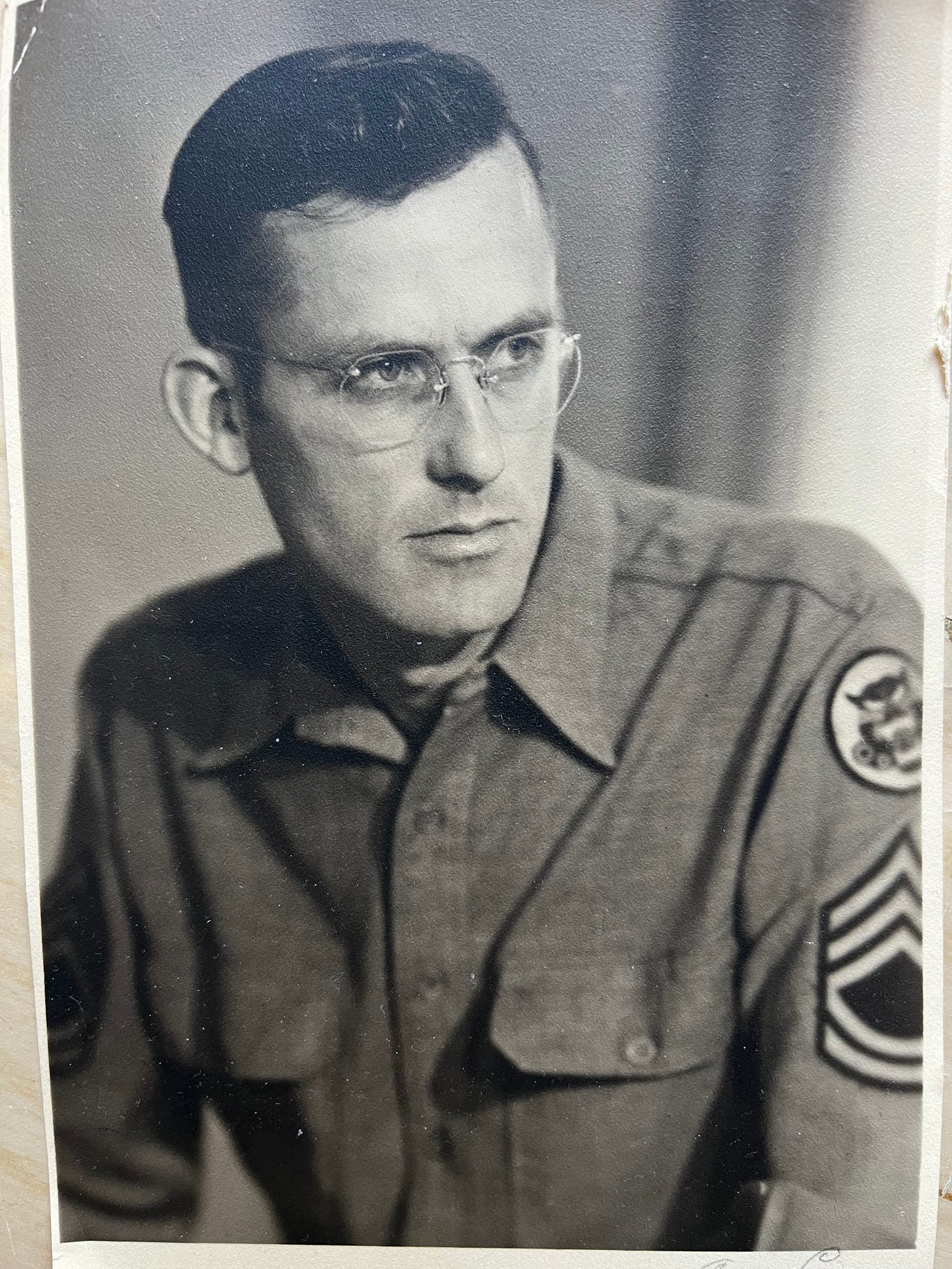

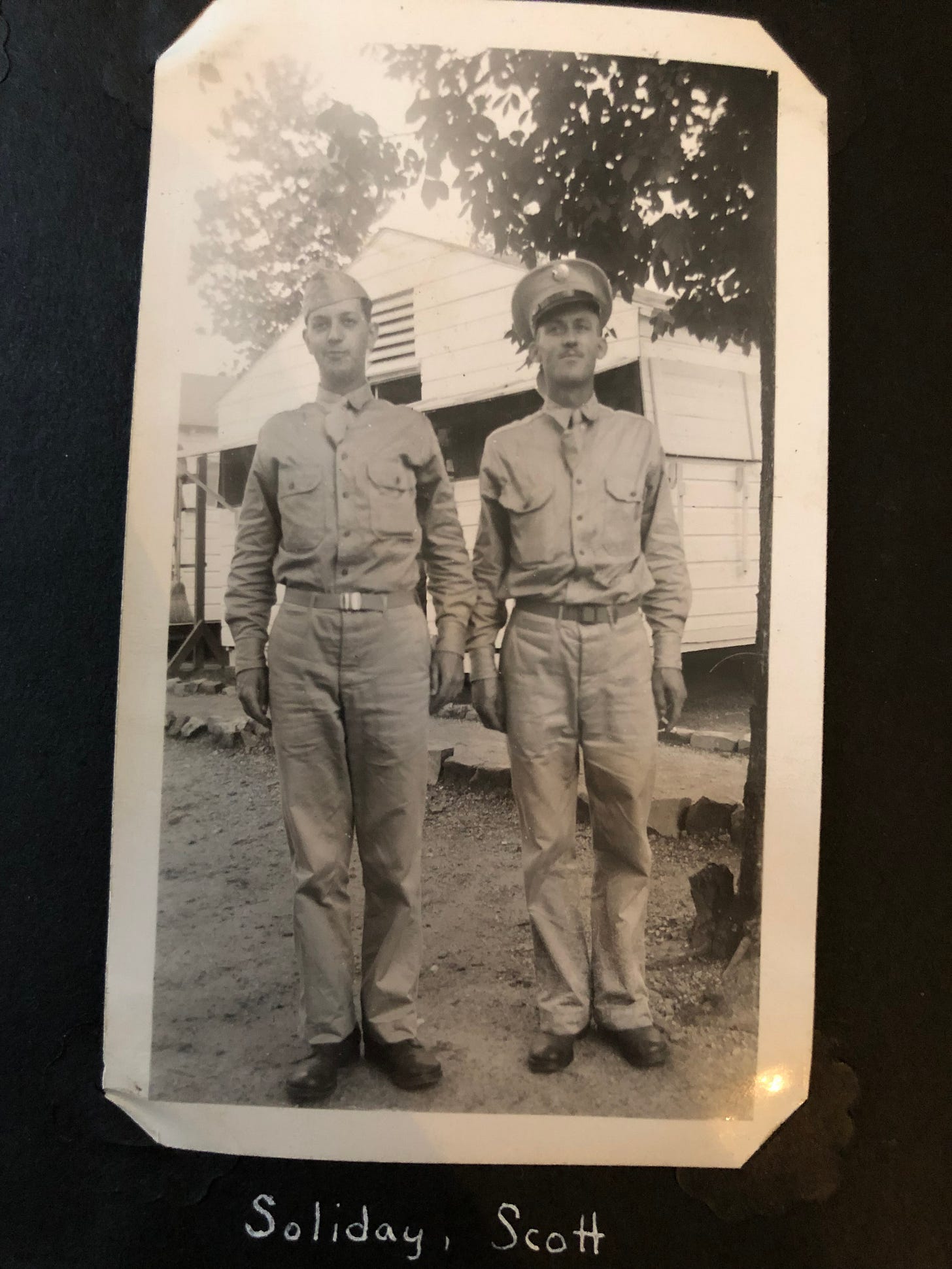

After the Battle of the Bulge, the tank-buster battalion took Scott, left, and best Army buddy, LeRoy Flick, to Germany. Heavy snowfall and bitter cold saw Scott lugging officers’ bulky sleeping bags (photo: anonymous US Army soldier)

Grandpa would use a messy mix of cursive and print, here relatively clear, through life.

At war’s end, Scott had reached the rank of corporal—not exactly what he desired.

***

The very Panzer tank-buster patch Scott wore on his uniform sleeve. Some of the elite troops were called “Black Panthers.”

Few war-time keepsakes would he bring back home, but one memento stands out among a sparse collection: a black-and-orange arm patch of a panther devouring a tank, stitched on Scott’s sleeve. Today, one patch belongs to my father and the other to me.

A dozen years older than many a private, he belonged to a tank-destroyer battalion charged with thwarting the feared German Panzer and other armored track vehicles that had wreaked havoc across France in 1940. In December 1944, with Nazi Germany losing serious ground, Adolf Hitler envisioned one final push westward, through Belgium, France and on to the English Channel, in an attempt to swing the tide.

Just one problem: The US tank-buster battalions and company were advancing head-on, via France, toward a Belgian forest called the Ardennes. German generals, by way of Hitler, called for a wedge to split through American forces. This wedge became popularly known as Bulge, coined in print by an American newspaperman. The name stuck and the Americans went on to win the battle, when temperatures dipped as low as zero degrees Fahrenheit (-18 Celsius).

A state champion typist as a high school senior, Scott tended to desk-top bureaucratic tasks and was out of the fray of combat. The bitter cold and snowfall saw him looking after the needs of commissioned officers, including lugging around sleeping bags belonging to lieutenants and majors.

“Boy, they were so big, you could hardly get an arm around them, and it took two of us to carry one,” he says of the officers’ bedrolls. “That really burned me up. Fact is, all we got was an army blanket, two at most.”

The northeast Wyoming kid who grew up on a dirt floor felt short-shrifted with the cards dealt to him. He wanted to be the one bossing people around. Cross body language in a family portrait speaks volumes.

***

The 1993 University of Wyoming football team is practicing just beyond the chain-link fence from Scott, a season-ticket holder since the early 1950s, along with his wife, Brownie, the granddaughter of ethnic Germans who lived a bumpy carriage ride away from Transylvania. Her quixotic dad, as in the film “There Will Be Blood,” would use a twig to divinely guide him to oil trapped below a patch of godforsaken Wyoming prairie. The cumbersome drill bit struck black gold, lots of it too, but obstinate old country ways, family squabbles and lawyers vaporized much of the petroleum proceeds over decades.

“Miller No. 1,” the name given to Campbell County’s first oil well, keeps on pumping.

Brownie’s battle-axe mom, Wilhelmine, stood just five-feet but ruled the roost through Germanic discipline, wielding small blacksmith-like forearms, the product of swinging a meat-cleaver as a butcher’s assistant to her husband Charles Miller, left, a laid-back quixotic soul. He lived to be 97, she 94. Both of their families emigrated from near Transylvania (photo: Brownie’s post-wedding photo album, assembled in Arkansas during Scott’s basic training).

He in his 90s and she in her late 80s, Charles and Wilhelmine beside the family oil well, Miller No. 1, in the 1970s. No Chinese-made steel here (Photo: Scott-family archives).

***

Scott’s mom and dad would have no such quandary wrestling over how to divvy up cash. There was none. As a boy, he saw a family member take off on an overnight trudge through knee-deep snow, all to bring back a sack of potatoes 10 miles off, or so goes the oral tradition.

My great grandfather Bert Scott, of Scottish stock, laid pavement and mined for a living. His wife of Irish ancestry, Lola Belle Patrick, saw over their kids as well a small farm and ranch. To be sure, they ate their share of cottontail rabbits, abundant to the territory, and corn cobs saw second duty as toilet paper. “Why, we certainly did use them,” Grandpa says stoically.

A rather down-on-their-luck American Gothic clan, the Scotts were homesteaders from Lucas County, Iowa, which they left in 1916 for dusty terrain outside Gillette, yet to become the energy boom town it is today. The family of seven lived in a ramshackle house, with compressed earth serving as a floor and a coal-fed stove providing flame for cooking and hand-warming. Bert’s face, shielded by a black cowboy hat, shows wear and tear. A shot of whiskey may have been welcome after a day on tar.

***

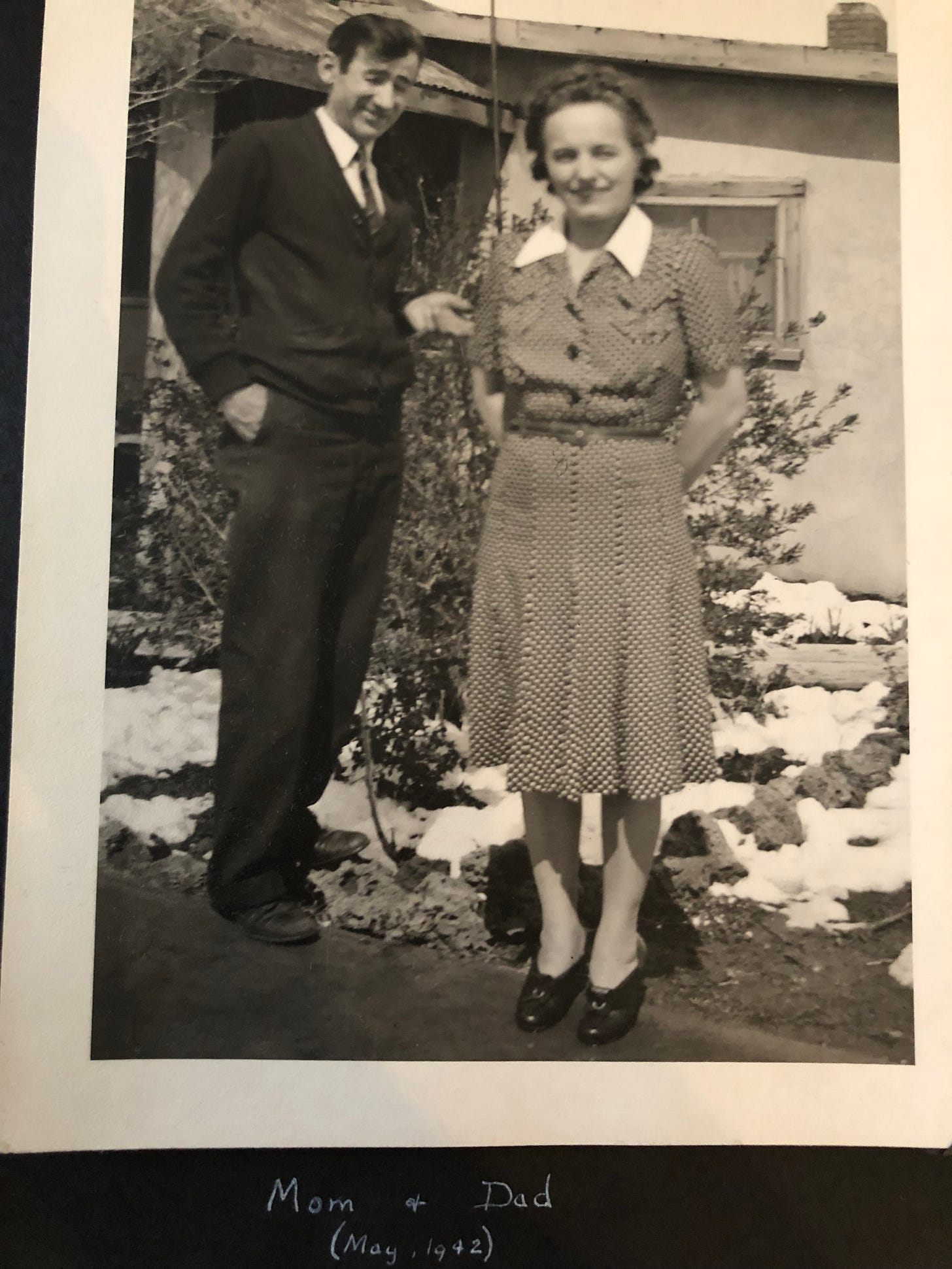

In 1941, Scott got wind of a pretty cowgirl who rode horseback to her job outside Gillette. Part tom girl yet attune to women’s fashion, she defied a schoolmarm’s definition. It’s a Wyoming thing. The brunette with the Indian paintbrush smile and quirky disposition would coax her colt on Sundays to maneuver across tricky ravines en route to her very own little school house on the prairie.

This called for romantic action. Others were courting the cowgirl teacher. Scott, himself an ex-teacher, won.

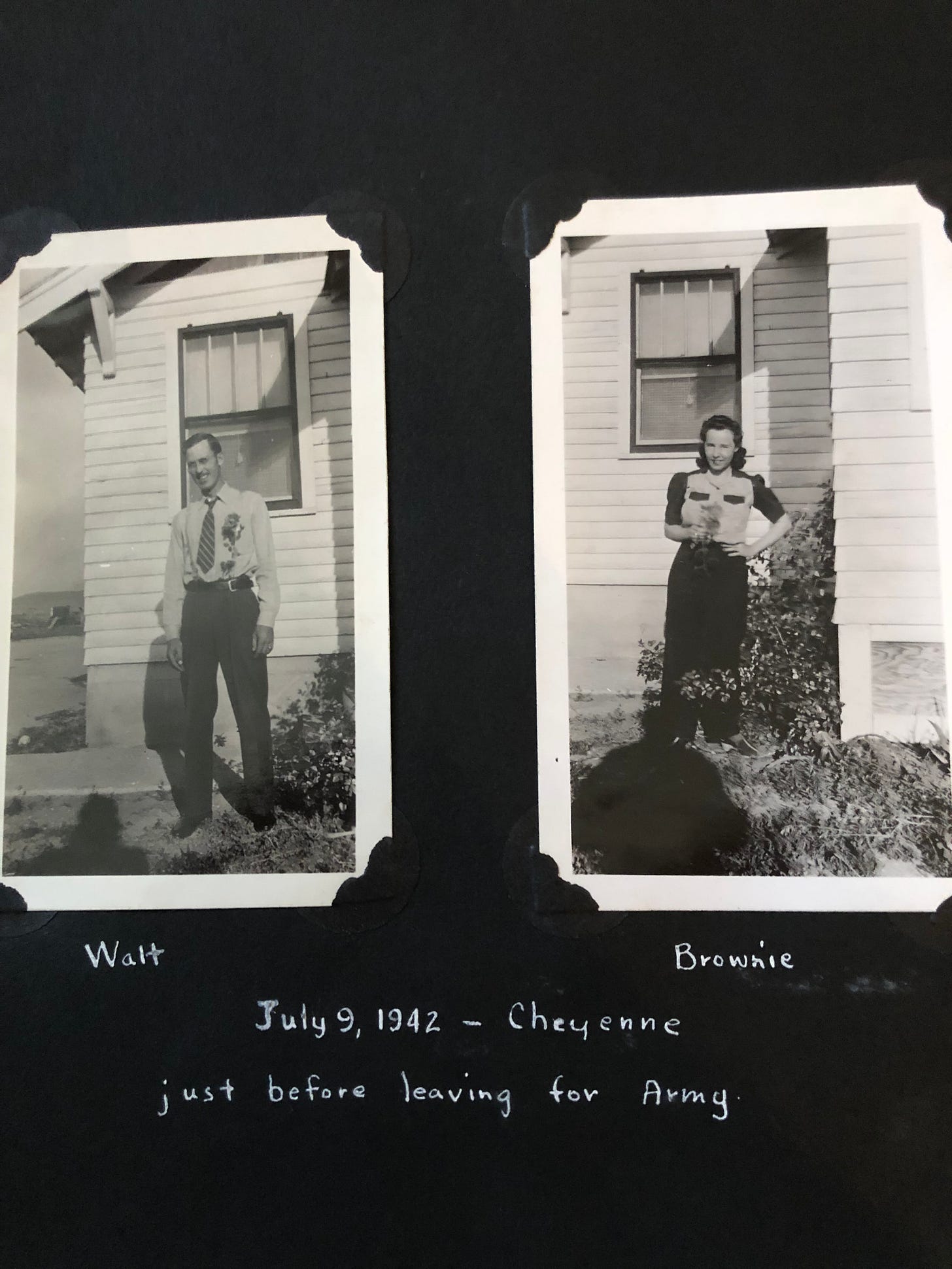

Walter and Brownie, against her Germanic folks’ wishes, would elope to Hot Springs, S.D.,—no pun intended— and leave a red-herring scent to their trail, signing wedding papers in Nebraska. They settled in Cheyenne, where Grandpa worked as a mail clerk on the Union Pacific Railroad.

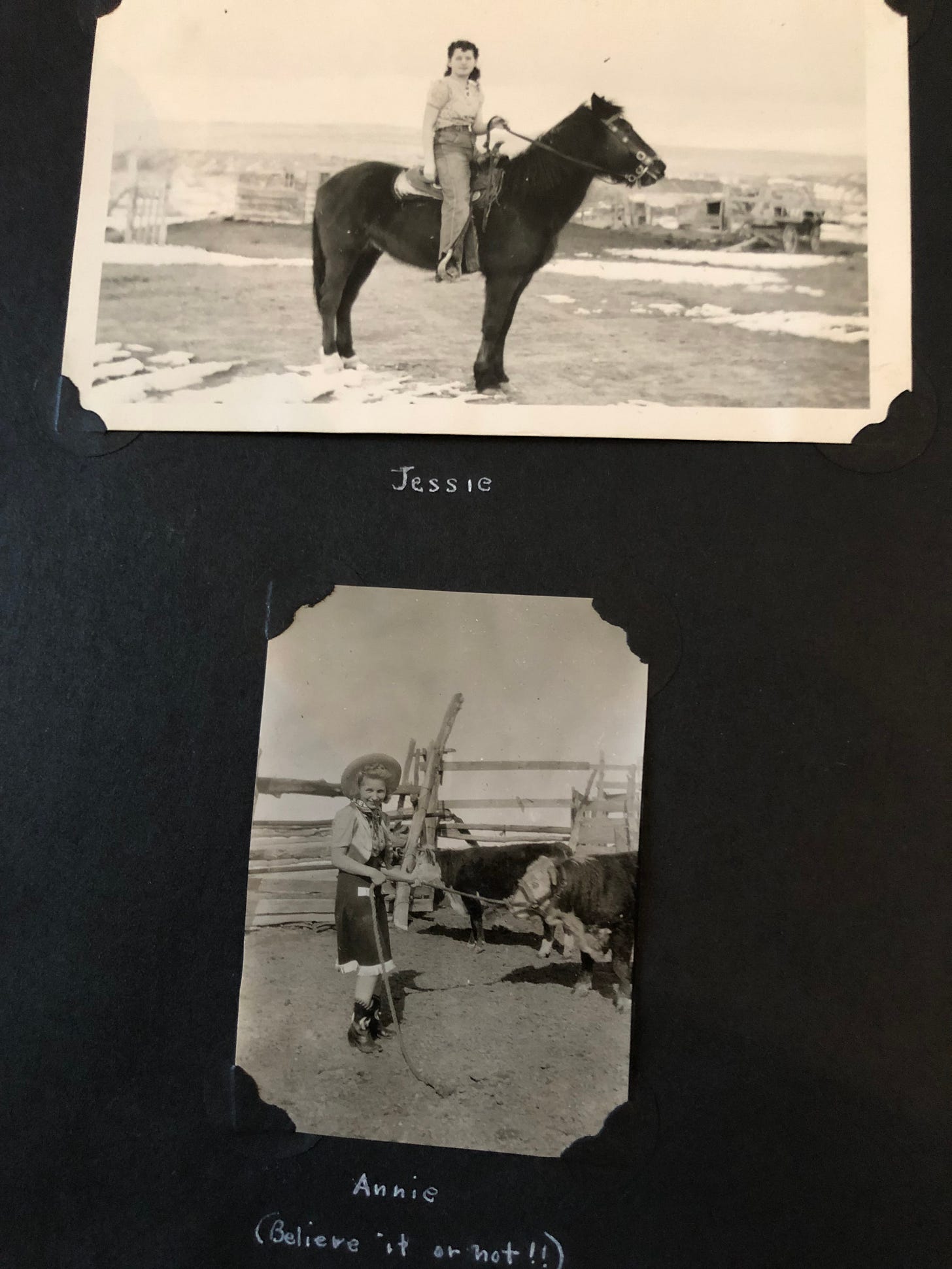

A single-room schoolhouse teacher raised as part cowgirl, Brownie dressed classily and had her fair share of suitors before Scott came swooping in.

Ranching ran deep in both families. Scott’s sister, Jessie, was an expert cowgirl. Brownie’s blonde sister, Annie—a looker who teased men—played the part as ranch hand, dressed to gitty-up guys.

Jessie breaks a bronco.

The two sisters-in-law got on well.

After a year, no baby was coming, and Scott was getting antsy as young men around him were getting drafted into the military. When Uncle Sam opted to help out Europe, even more got tapped.

Scott was pushing 31, had a good job with a handsome pension system, and loved Brownie. If only he could break on through and really be somebody. Was sorting envelopes on steam trains really what he wanted as a career?

Again, Scott turns to Grand Avenue, props his hands behind his head, and calmly says:

“I enlisted.” Somehow, he doesn’t seem proud.

This was the plan. He had been a public-school teacher who led young men, was a swift typist, and ate up anything with numbers, spending spare time pouring over his bank statements, occasionally finding cents’ worth errors. It was the stickler for detail in him.

Scott wanted to be an officer, a guy with a little clout for once. A second lieutenant would do just fine. When he got to basic trading in Arkansas, it went like this, in so many words:

“Walter Scott, you do not have a college degree. Your name will now be Private Scott. Welcome to the United States Army . . . Next!”

Brownie, planted across the living room in an Easy Boy armchair, remembers the day: “Boy, he really got rooked, but that’s the way it goes.” She giggles a nervous tee-hee. The cowgirl-turned granny, speaking as if the undefeated Pokes had just lost the 1968 Sugar Bowl, returns her focus to live TV coverage on the Branch Davidians and David Koresh.

The rise-and-shine to brass bugles wasn’t all that bad. Outside the barracks in Arkansas, Brownie was there in a Victorian-crafted house for women only. A little something rather would be conceived.

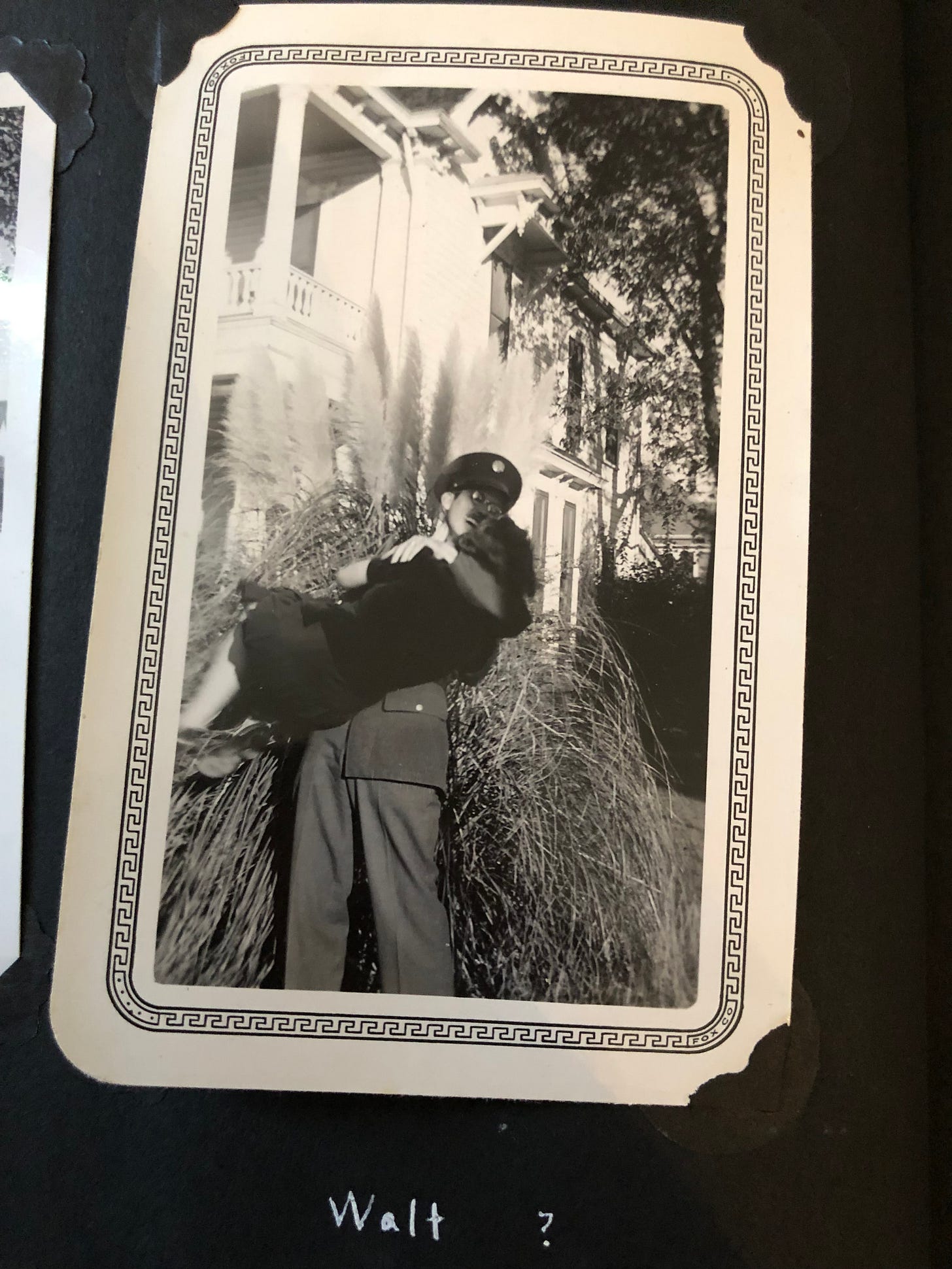

Walt Scott, with Brownie, celebrates finishing basic training. A while later, she discovered a little something rather had been conceived. Ikey Scott was born a war baby in wait for his dad, who was fighting abroad.

Brownie had room and board in a Victorian-style house for women only. They still found their ways to meet up.

Getting closer to shipping out, ten-hut.

***

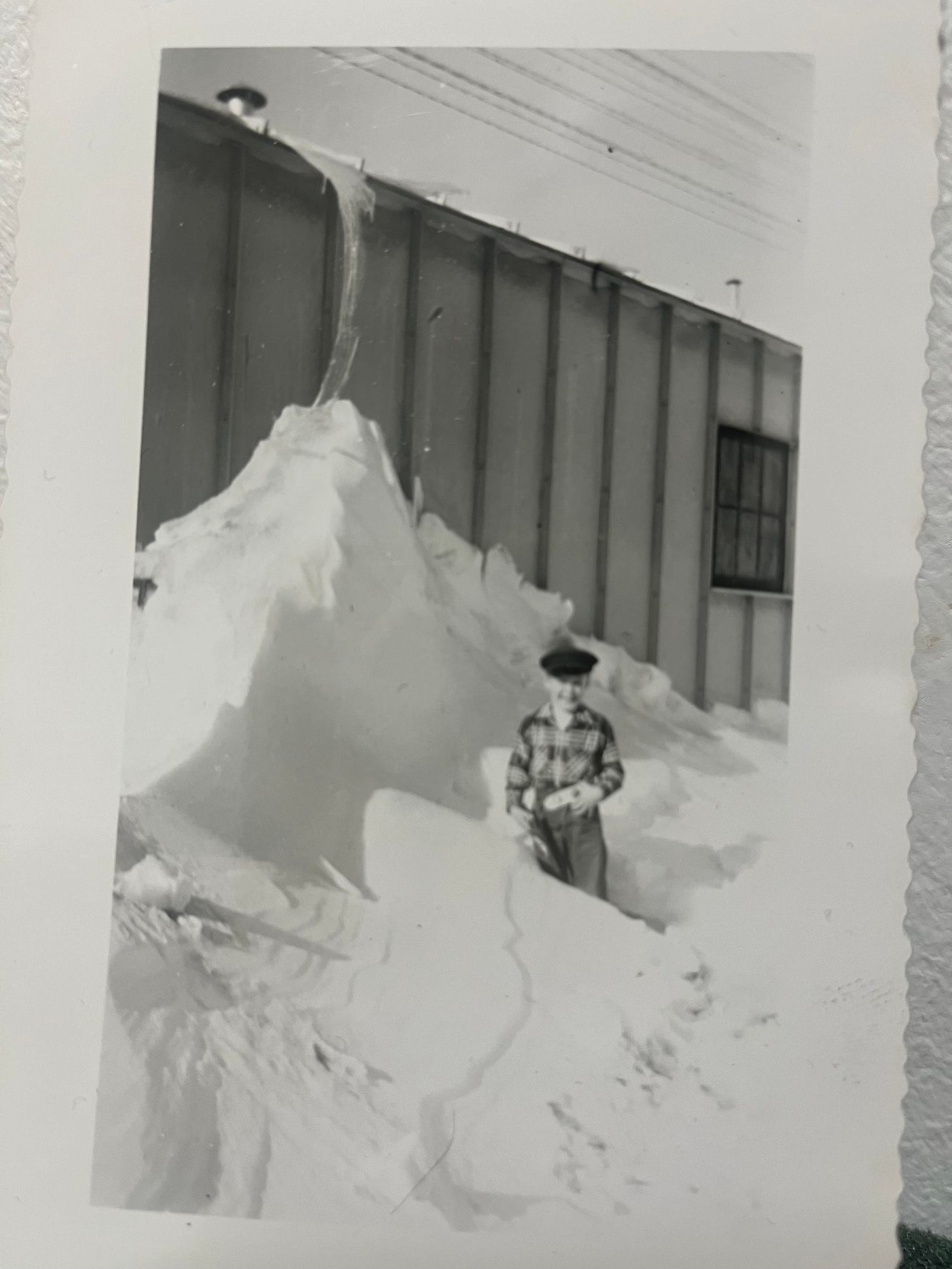

The Blizzard of ’49, which pummeled mail trains in their tracks and dumped eight feet of blowing snow over much of the state, has finally melted away. A six-year-old war-baby boy is bouncing a ball outside the Butler Huts, proletariat UW housing for married couples.

Another kid approaches “Ikey” Scott, nick-named after General Dwight D. Eisenhower—a key cog during World War II—and wishes to join in the fun. After pivoting away, Ikey says no, “It’s my ball.”

A father comes out and spanks Ikey on the bottom, telling him: “You share that ball with my son, young man.”

Ikey cries.

Walt Scott, rest assured, is watching from his kitchen window, having just washed bacon grease off the frying pan. He throws his glasses and the apron off.

Hell has fury struck.

Dressed in a crisp white T-shirt and slacks, his usual off-cuff blizzard attire, Scott comes running out and squares off with the dad.

“Why, you have no damn right to touch my son like that,” he says. “You’re gettin’ a beat-down.”

Ikey Scott playing in snow drifts piled against UW’s Butler Huts. The Blizzard of ’49 shut down trains and much else.

***

The hulking Challenger steam locomotive screeches into Laramie, hissing and huffing to a slow roll in September of 1951. Out steps a postal worker fresh off a double shift—or was it a triple?— that saw him get back on board in Ogden, Utah, 12 hours earlier. Walt Scott is carrying a produce bag of grape-fruit-sized peaches he bought fresh off the farm there. “Juiciest dang peaches you’ll ever taste,” the 39-year-old plans to tell Brownie back at the Butler Huts.

Like clockwork, a loyal law-school buddy hands off meticulously scribed notes for classes Scott couldn’t attend the last two days. The pair of aspiring attorneys, one 16 years junior to the other, chat briefly through a cloud of soot wafting across the Union Pacific railroad platform. Scott folds the notes into a leather satchel he keeps for his studies on civil and penal law. It’s been a tough ride as a full-time mail-car clerk—a job he got back after the war—when precious breaks are spent hunched over text. A lurch sometimes slops scalding hot coffee over fountain-pen scribbles, especially when he’s nodding off.

The Union Pacific Challenger, here pictured in Laramie in 1994 during a ceremonial run from Cheyenne, pulled Scott’s mail-train cars over steep terrain (photo by David Scott).

In Laramie, two engineers grease up the Challenger’s 4-6-6-4 wheels, among the biggest of any steam locomotive (photo by David Scott).

At UW, he is going into the last of four years on campus, a grind to beat all grinds. His wife and young son deserve more attention. Even still, President Roosevelt’s GI Bill is paying the tuition, and that kid law-school student, the one with the folksy silver tongue, has proved invaluable.

That college kid would be Gerry Spence, who turned out to be the most heralded trial lawyer of his time, scoring jury verdicts in cases for Randy Weaver at Ruby Ridge; Karen Silkwood, played by Meryl Streep in the 1983 film “Silkwood;” and Imelda Marcos, the former First Lady of the Philippines. The list goes on.

Spence and Scott see something in each other. They are, in a certain sense, polar opposite. Spence is the charismatic speaker who could, with proper preparation, talk a mama bobcat out of her den. Not nearly as polished at playing to a jury, Scott is adept at working behind the scenes, catching precedent and technicalities, facts and figures.

He has an irksome sense of justice, which he would later use to lecture an officer on the stand: “You had no right to tail the defendant for 15 miles before turning on your siren. Next time, govern yourself accordingly. Case dismissed.”

The gavel comes down with an ear-curdling smack.

***

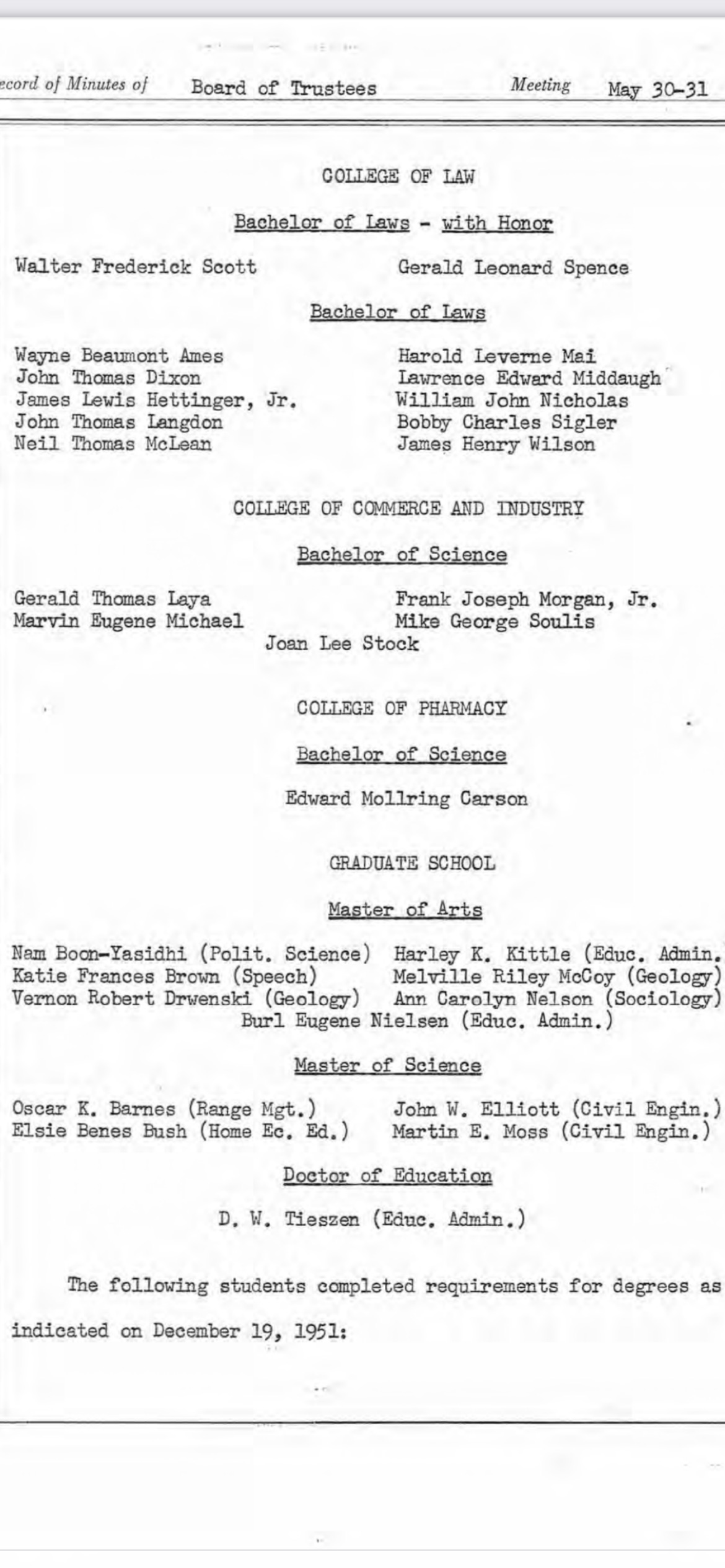

In May, nail-biting time rolls around. Four years of exam scores and grades are tallied for the 1952 UW law-school class. Walter Frederick Scott, a month shy of being 40, has graduated:

No. 1.

-30-

Lisa:

Glad you appreciated the Midwest part, all else. Yes, if we go back far enough, many of us might find our roots in corn-field country. Walter Scott would have been a more realistic example of a guy fighting for the American Dream. Hard to fathom how that generation got up into their 90s, with all the turmoil. “The Graduate,” starring a young Dustin Hoffman, is famous for the line, “Plastics.” What does that word mean now?

An engaging sweep of the 60 year history of a family. It tells of how the mid-west used to be and how strong the people were and still are. How wonderful to really get to know your grandfather. He was a good example of someone who never gave up on his dreams. And with the possibility of another world war on the horizon, we must remember World War II. Your description about corpses across the continent is bone chilling. Yet, that’s how WWII was. That war united our country in a common effort. We lack such unity now. The photo layout is just like looking through the family album. Please write more like this!