Locarno, Italy: where an asparagus festival tempts, like lush grass to rabbits

The Piedmont mountain feast depends on butter, little used nowadays by Italians.

Roberto shows one way to eat asparagus, sliding the spear in by hand.

The woman fidgets as ceramic bowls the size of hefty watermelons are set before hungry diners seated beer-hall style.

Inside the terracotta tempt thick stems of asparagus submerged in a rich liquid.

“But how much butter did they use?” wonders Daniela Savio, 54, gestisculating with both hands between cross-talking anecdotes. “No way, how mind-blowing.”

A housewife, she and her husband, Gianluigi, 58, an electrician, are seated at a long wooden table, one of a half dozen warmed by attendees within an ex-parochial stone palace, where chatter among diners—tummies primed with three types of bread and cold-cuts each—is rising as surely as cafeteria din the Friday before prom.

Daniela Savio plates shoots. “But how much butter did they use?” she exclaims.

This is Locarno, Italy, where I-know-you communal cheer comes easily, even on a Tuesday federal holiday that observes the country’s liberation from Nazi Germany.

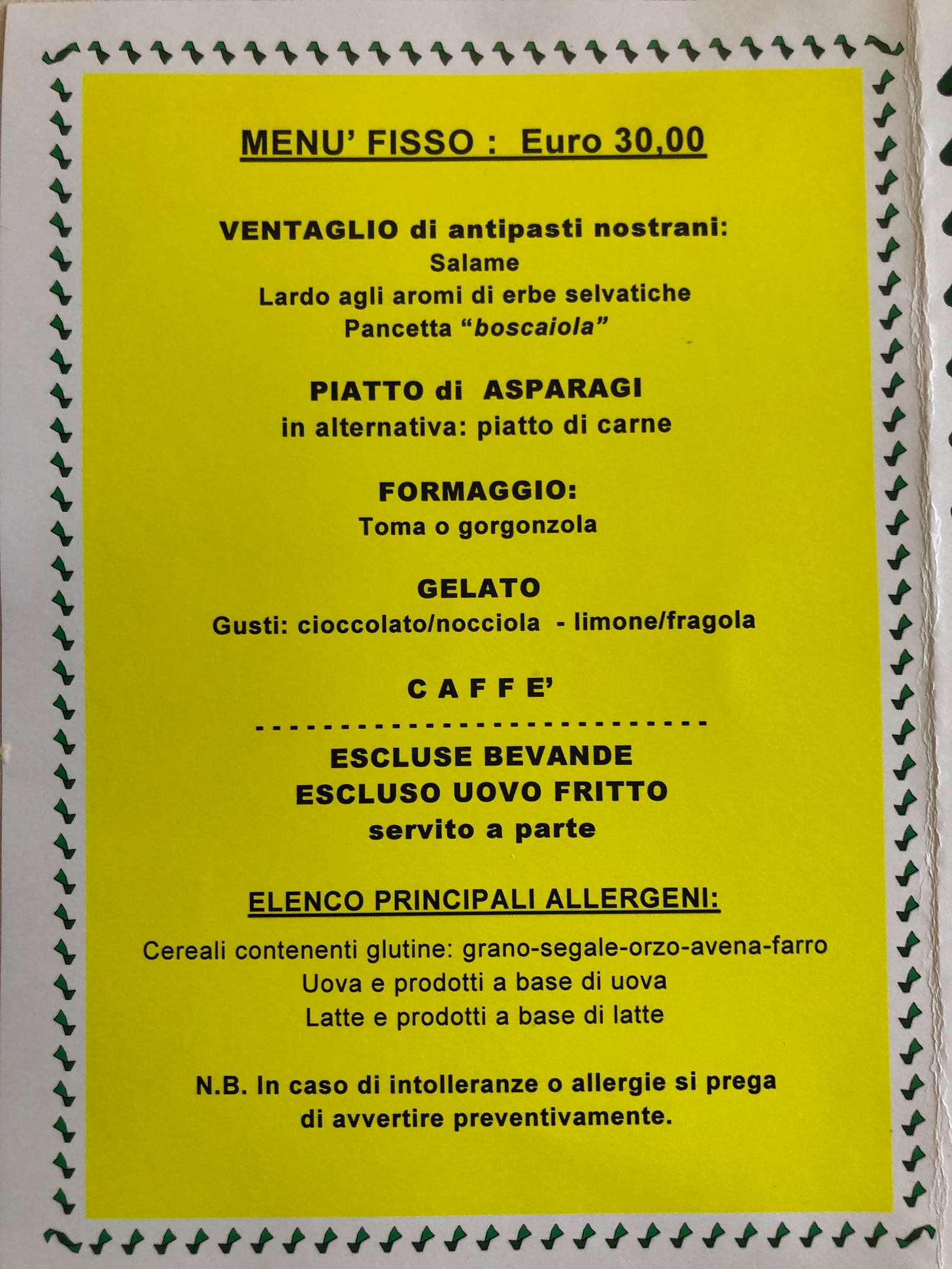

Reservations were made weeks in advance. Without one? Fo-gedda-about it, sold out.

For the big eaters—buona forchetta—forking the tender vegetables is an annual rite, part of the village’s 29-year-old festival on asparagus, spread across a four-day weekend in the Sesia River valley village, on the road to high-altitude Alps peaks, glorified in spring sunlight as in an Albert Bierstadt painting.

A gnome pipe-smoking asparagus.

Clouds burn off after lunch ends on a national holiday, April 25, observing Italy’s liberation from Nazi Germany.

Asparagus diners file into a 125-year-old palace.

A server named Canotta, his long hair wildly gelled to meet 80s-rock-band standards, estimates 1,543 pounds (700 kilos) of asparagus were shipped in to meet demand.

The rocky valley terrain has never been particularly suited to asparagus, which is not grown here, but that didn’t stop a retired banker—if just for one week—from shifting meat-and-rice-based palates to thick edible grass shoots.

“It’s my idea,” says Primo Vittone, a spry 81-year-old local who joys in promoting his community through a tourism club, Associazione Turistica Pro-Loco Locarno, for which he has been secretary 57 years. “I thought of the sagra (festival) of asparagus to attract people to the town.”

Swiftly wiggling and weaving through the dancehall-sized dining room, he is truly loco about Locarno. Not far from the mountains, he gestures, lies fertile farm land—today used to grow rice—that would soak up asparagus, a plant that thrives in salty maritime-area soil.

“Last century, there was a territory perfectly adapted for the cultivation of asparagus,” he says before pointing up to the burg’s proud stone church, high in the hills.

Primo Vittone, a retired banker, came up with the idea for the asparagus feast.

Before stepping into Locarno’s hillside church, Vittone instructs: “Keep your eyes closed, walk five steps, then look up.”

Locarno has unusually friendly felines.

Like rice likes water, asparagus needs terrain “that doesn’t let water through,” as on alluvial flood plains, found a half hour’s drive away in neighboring Piedmont flat lands that extend toward Milan, to the southwest.

Piedmont grows the most rice of any region in Italy, where up until about 1960 most north Italians ate risotto, not pasta—and when olive oil played second fiddle to butter, inconceivable today.

“You have to remember that up through post World War II, north Italy used butter for cooking, not olive oil, so a feast like today is rooted in tradition,” says Angelo Rainoldi, 59, who has a house not far down the valley and goes to as many area cuisine-themed feasts as he can.

Angelo Rainoldi, one of more than 100 lunch-time goers: “You have to remember that up through post World War II, north Italy used butter for cooking, not olive oil.”

Matteo Delgrosso, 45, is president of the Associazione Turistica Pro-Loco, which made the meal.

Today, the roles are reversed, as in olden times, when butter is crème de la crème, drowning asparagus.

The cradled puddles of butter—or burro—keep the green vegetable juicy, Vittone says.

“If you don’t put much butter on (the asparagus), it remains dry.”

As with eating fish and seafood, a couple techniques are employed to most easily gobble up the greens, generously topped with Parmigiana cheese as if one dairy product isn’t enough. A quick scan reveals most female diners using knife and fork to sever the shoots from their stalks, themselves eaten down to the last three inches.

Nino Argia, 71, left, goes by hand while family friend Graziella prefers knife and fork.

Some of the men, though, scoop up the spears by hand, as with cinema popcorn, and slowly munch the dangling stalks. Nobody’s checking on table manners.

“This is the best way,” says Rainoldi, reaching for a fresh tip oozing with butter.

As with shellfish eaters, every two guests has a bowl to discard the much chewier bottom stem.

A bowl used to discard the woody ends.

A good hour is spent like rabbits nibbling on tender grass—but the show’s not over, as happens during big Italian meals.

A team of servers, hustling like Lufthansa flight attendants, shuttles over small plates of Toma cheese, made from cow milk. The diners’ pace has slowed, and a few of the cheese dishes go untouched, with stomachs getting gorged.

That’s it’s—but wait: There’s Ice cream.

Basta—enough.

Uh, no.

Two rounds of fruit-based liqueur are sipped the last half hour. They help with digestion, goes the Italian thinking. Waiters cajole diners into a final round, when a last table tale revolves around the most widely spoken language in the world.

A server hands off fruit-based liqueur, used for digestive purposes, in this case to Franca D’Oronzio, who is telling a tale on London Heathrow.

“This is why English is so important,” says Franca D’Oronzio, seated down the table beside her husband, Giovanni Magistrelli, 59. The couple spend half of each year in Porto Santo, Portugal.

“Try explaining to a Heathrow Airport agent why you only brought your identity card and not your passport,” she says in Italian, dabbing a napkin to mouth corners. “I tried my best, but English doesn’t come so easily to me.”

What came easily to everyone today?

Slicing through buttered-up asparagus.

-30-

An American digs into asparagus.

A whole lot of cuisine

An Italian, Giovanni Magistrelli, right, justifiably whips an American at foosball

Looks good! I don't remember ever eating it as a kid, but I like asparagus now. You seem good at finding festivals!